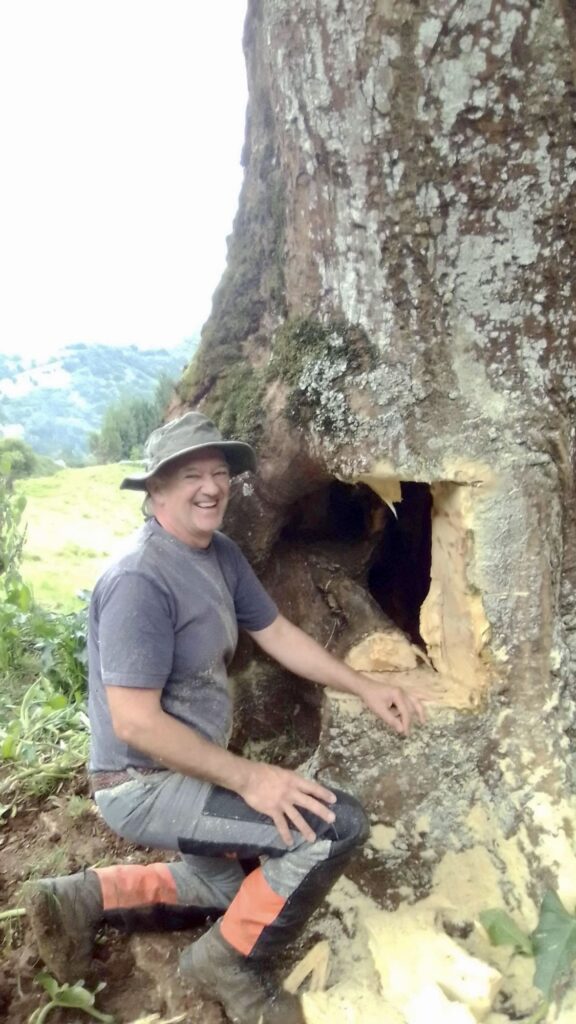

High steak situation: the cow that got stuck in a tree

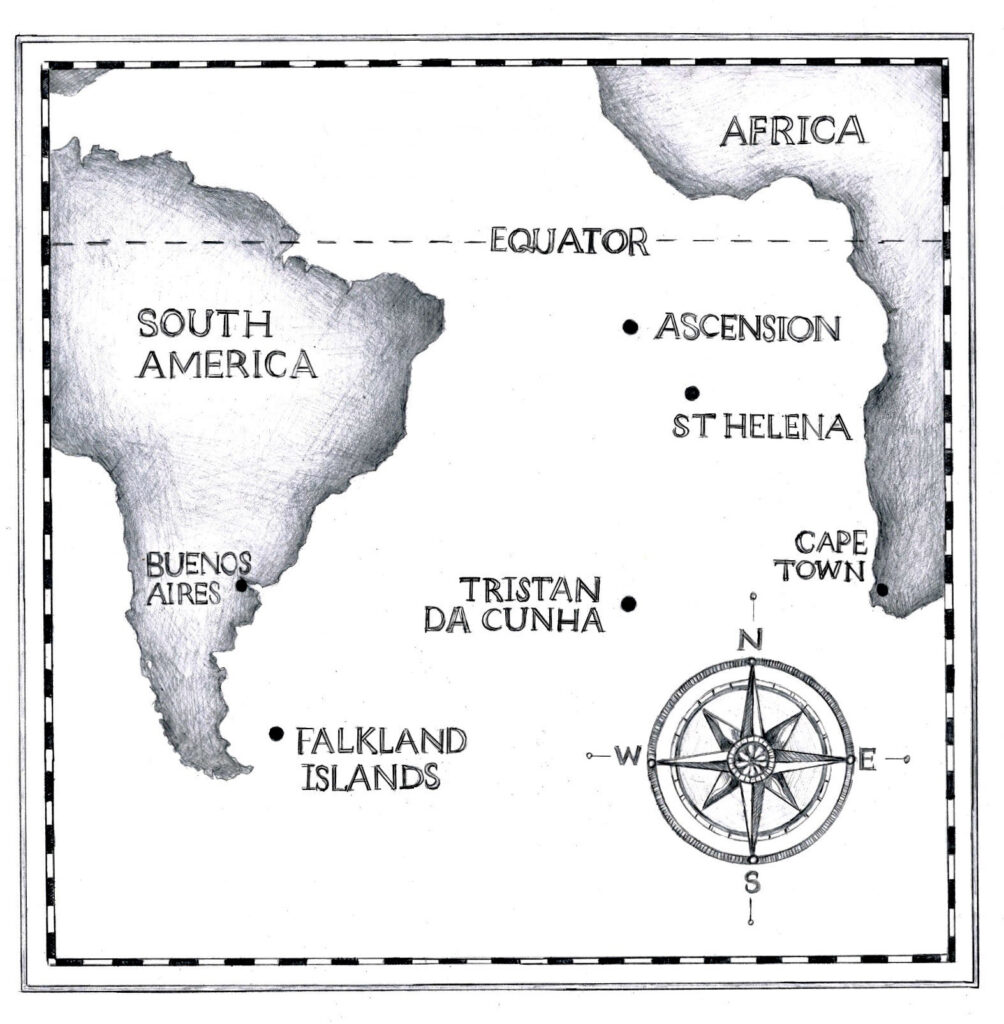

Jonathan Hollins has experienced some odd animal encounters as overseas vet on the South Atlantic Islands of St Helena, Tristan da Cunha and Ascension. But none top the time when he faced a cow that got stuck in a tree…

‘Crikey! How in hell…?’

It’s not every day a vet is forced to discard his scalpel and operate with a chainsaw, but my day had come.

We all – farmer, farm workers and vet team – gawped in bemused astonishment.

The cow that stood before me had done something I would never see again in a host of lifetimes, and created a spectacle that would enthral the whole island of St Helena.

Refusal as a vet is not considered an option

I was still working on the text for my memoir Vet at the End of the Earth with my fabulous editor Rowan Cope, when my mobile, that duplicitous friend and foe, had trilled in my pocket.

It had been the police station.

Could I go and attend to a cow stuck in a tree at Mount Pleasant? A rhetorical question politely put since refusal as a vet is not considered an option.

Mount Pleasant is owned by merchant Greg Cairns-Wicks and his conservationist wife Becky, a well-run farm set in beautiful scenery with Napoleonic connections.

I knew it well, not least because I had bought the adjacent land, complete with ruined Georgian mansion and coffee plantation throttled by dense jungle.

This meant that, fortuitously, my Land Rover was stashed with forestry equipment, and I’d become a pretty dab hand with a chainsaw.

The weirdly puzzling sight stopped me dead in my tracks

I had clambered up the steep field towards the waiting group, ballasted with axes, sledgehammers and wedges, and rounded the grey amorphous trunk of a huge thorn tree, expecting to find the cow jammed in a branch.

The weirdly puzzling sight stopped me dead in my tracks.

Sure, cows get their heads stuck: in discarded feed containers, railings and fences. But this trumped them all. It was a headless-cow-tree.

The cow seemed melded with the very wood itself, like some ghastly hybrid from H. G. Wells’ Island of Dr Moreau.

Not one gap marked how she had managed to force her skull through an impossibly meagre hole in the hollow trunk of this Tolkienesque giant, but a wide arc of paddled mud indicated she’d been there some time.

If she stumbles even once, she’ll hang

I squeezed my hand along the cow’s throat and felt around her neck. It was as tight as a gargantuan cork in an absurdly large bottle.

‘Can you sedate her?’ suggested Greg. ‘Then we can drag her out.’

‘No chance. Her neck is tightly baled. We’d hang her. In fact, if she stumbles even once, she’ll hang.’

Greg was holding an electric chainsaw and I reached out for it.

‘No, I’m afraid not,’ he said, shaking his head and drawing it back. ‘I started it up and she went crazy.’

‘It’s the only option, Greg. And frankly if I gash her, I’ll just have to stitch her up. Otherwise, she’s going to die.’

A brutally accurate assessment.

I’ve never used a chainsaw so delicately and precisely as on that day.

The chainsaw had indeed become my titanic scalpel blade

‘First, make a bold incision’ is the classic imperative of the older, respected surgical texts because if made with a tremulous and hesitant hand, that incision will end up with tramlines and crossroads.

But given a steady hand, I love the definite and purposeful accuracy of a sharp scalpel, cleanly incising to the correct depth, length and angle with controlled and focussed dexterity – sometimes demanding nerves of steel and a dash of composure.

The chainsaw had indeed become my titanic scalpel blade, parting wood from flesh. The ‘boldness’ here was of the refined variety: virtually no pressure on the chain less I performed what the lumberjacks call a ‘plunge cut’ – which would literally be a bloody disaster and paint my face red.

I was going to nick her – it was just a question of where and how deep

All my senses were on high alert, legs braced, frog-like, to leap back when she swung towards the speeding chain, which she did on several occasions, and with sang-froid pouring copiously through my veins to steady my hands.

After an initial frantic reaction, the cow settled, the vibration of the saw seeming to be in some way soothing or even hypnotic. It was as well; on the horizontal slice I worked the chain to within a thumbnail’s distance of her bulging neck.

Here the wood was a perilous and challenging six inches deep and I could only stare at the print on the chainsaw’s bar to estimate progress.

I was going to nick her – it was just a question of where and how deep.

Now covered in sappy sawdust, I worked the tip of the chainsaw into the hollow interior where I thought her head was probably clear, feeling minutely for the give of less resistance, and leaving the neck until last.

It was going to hurt. Closer, deeper… any moment now…

The cow bucked as I skimmed her hide. The block came free.

She backed out, blinking in the sunlight.

It looked as if she was choosing a victim; we all backed off in comical slow motion

The backs of her ears were raw from her efforts to escape and she was sporting a neat souvenir graze on her neck.

For a moment she stood stock-still, eyeing each of us up in turn with a quizzical expression, almost as if to say: ‘Well what on earth was all that in aid of?’

It looked as if she was choosing a victim; we all backed off in comical slow motion. But Greg’s cows are well handled, and with an ungrateful snort of disgust, she finally turned away and sauntered off to join the herd.

The atmosphere was euphoric. ‘I have to say, Joe, you held your nerve there,’ Greg said, through his relieved laughter. ‘And thanks. I’m immensely grateful. She was pregnant – a valuable animal.’

‘Pleasure Greg. That’s the first time I’ve swapped a scalpel for a chainsaw!’ In all honesty, I had enjoyed every moment.

When we put the story in the local paper, it was a sensation. The people of St Helena have seen a thing or two, but a headless-cow-tree? Now that’s something new.

Enjoy more adventures with animals on the South Atlantic Islands

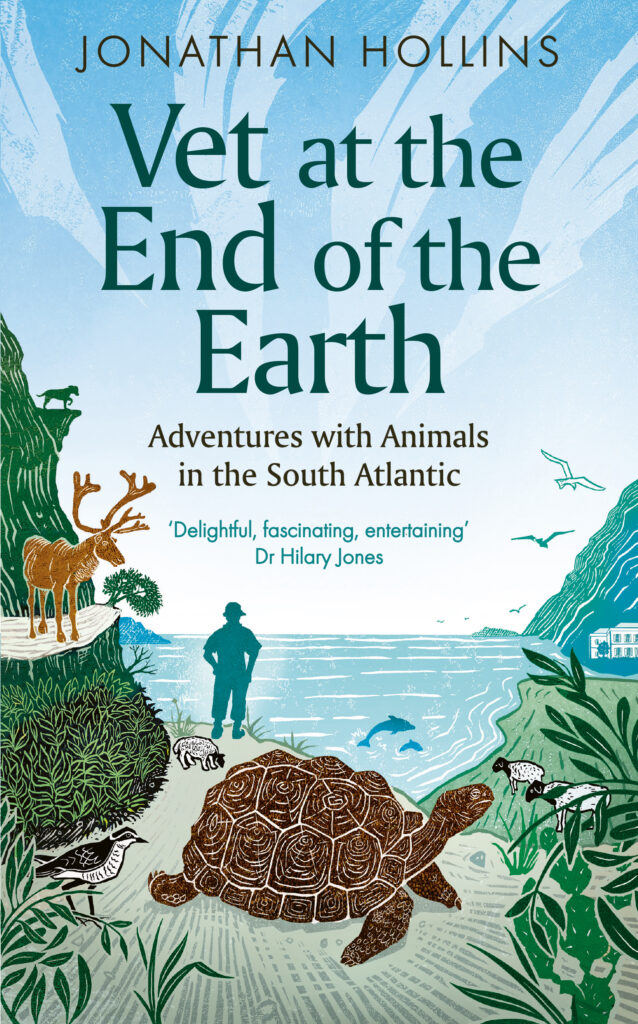

As you have witnessed with the headless-cow-tree, Jonathan Hollins has a vet’s life with a difference.

His tales are full of wonderful creatures and steeped in the unique local history, cultures and peoples of the South Atlantic islands, far removed from the hustle of continental life.

You can enjoy them all in his hugely entertaining and affectionate memoir, Vet at the End of the Earth – out now.

‘A delightful, fascinating and entertaining book’ – Dr Hilary Jones MBE

The role of resident vet in the British Overseas Territories of the Falklands, St Helena, Tristan da Cunha and Ascension encompasses the complexities of caring for the world’s oldest land animal – a 200-year-old giant tortoise – and MoD mascots at the Falklands airbase; pursuing mystery creatures and invasive microorganisms; relocating herds of reindeer; and rescuing animals in extraordinarily rugged landscapes, from subtropical cloud forests to volcanic cliff faces…