The Early Bird Catches the Boat to Egg Island

Jonathan Hollins recounts his adventures on Egg Island, cataloguing the species that call the northern shore of St Helena home, and staying downwind of the signature scent

There’s a reason Egg Island glows like the summit of Everest in the sunlight. And it isn’t snow.

It’s bird shit.

Or to put a more genteel gloss on it: guano.

Such was guano’s value, and the abundant fertility bound within its fishy phosphates that it was nicknamed ‘white gold’.

On the offshore islets of Namibia some 1,000 miles across the Atlantic – and before the advent of artificial fertilizers – gun battles were fought over the possession of the thick deposits left by millennia of abluting seabirds.

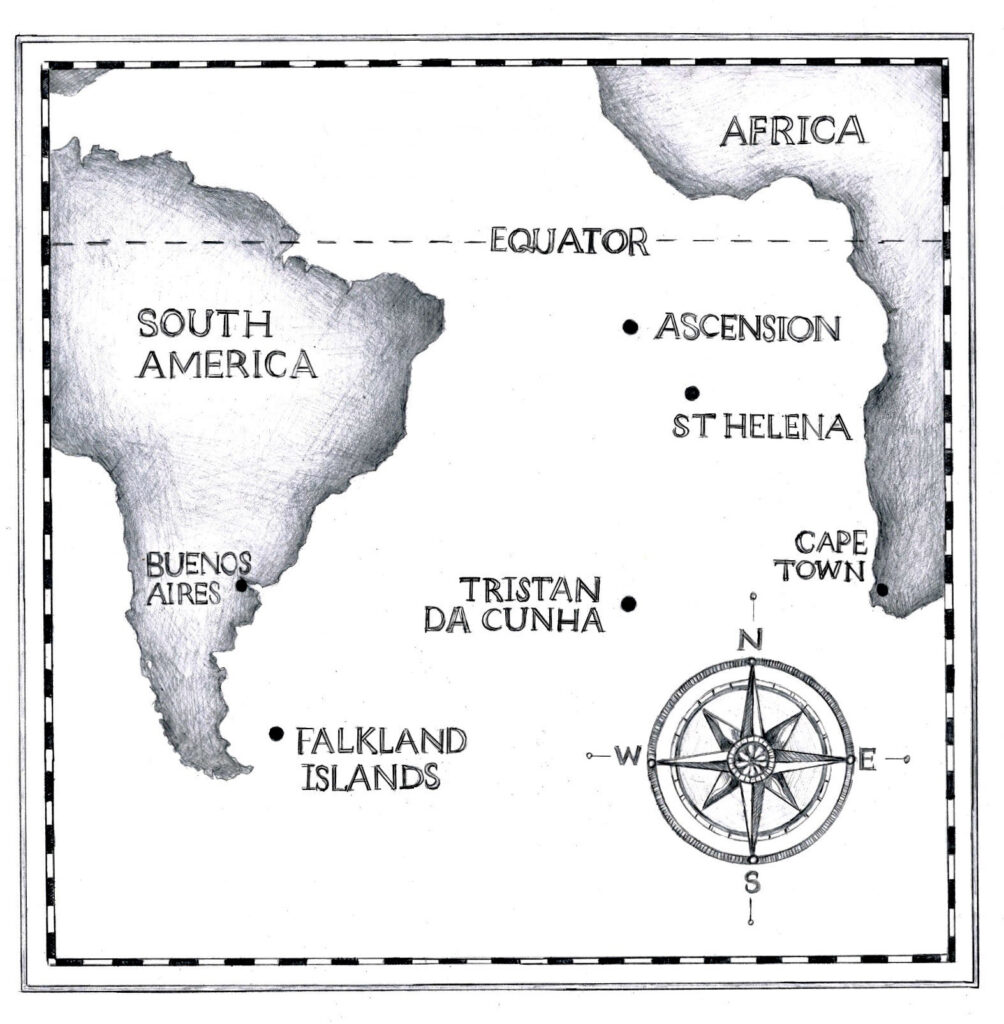

But on Egg Island, shaped like the protruding knee of a Titan on the northern shore of St Helena, it was a more placid affair: men on ropes chipping off stalactites of guano from the nests of brown noddies and dropping them into the cutters below.

The practice of harvesting guano has now stopped because Egg Island is a nesting site of international importance. And the reason for that is blessed absence of rats and cats.

And the reason for that is blessed absence of rats and cats

Setting aside the colonies of cliff dwelling noddies and the occasional magnificent long-tailed tropic bird, the majority of the nests belong to the charming and diminutive Madeiran storm petrels: ‘stormies’ to their friends.

The first challenge is always to get on the island. I was visiting in a purely veterinary capacity at the request of seabird guru Annalea Beard, herself birdlike in stature and wholly at ease with her feathered friends.

Johnny Herne, a local ‘Saint’ boatowner and a masterful helmsman, backed the stern of his vessel with meticulous care, his eyes pinned to the near vertical but jagged, seaworn rockface as he countered the surge of the sea with gentle thrusts of forward and reverse on the propellers.

Only in the scant few seconds when the rise of the water, the stern, and a set of particularly grippy ledges all co-align in perfect harmony is the leap made. At the urgent command of the crewman, we sprang across the gap and latched onto the rockface with steely decisiveness: hesitation is a recipe for dousing and a potential encounter with propeller blades. Sometimes I truly bless my simian roots. From there it’s a steep rock hopping climb up the Titan’s thigh to the knee.

From there it’s a steep rock hopping climb up the Titan’s thigh to the knee

A rounded summit with a large gun emplacement, its dismounted cannon pointing impotently out to sea beside a cocoa-stone bread oven hosting not loaves but an angry tropic bird incubating her eggs.

The island is not a hangout for the nasally sensitive. It steams and welters in the heat and humidity, enveloping the hapless visitor in a miasmic wave of ammonia and last year’s fish paste, potent enough to tear up the eyes. For now, I was the hapless visitor – and yet despite this noxious onslaught I was relishing every moment.

The stormies’ nests are strewn over the summit, in areas so dense that every footstep must be chosen with extreme care. Some of the nests are natural, under the cover of shattered rocks, others are small villages of roofed flowerpots with rock porches created by the conservation team to encourage breeding.

Each has a house number on the underside of the lid. It was nesting time, and the pair of us worked our way through the villages, checking for eggs, fluffy newly hatched chicks and adults, calling out ring numbers when found, ringing when not. For this, Annalee is an adept, wielding pliers with surgical delicacy around legs as thin and brittle as matchsticks. But my skill, DNA blood sampling, was equally as fine.

Stormies are the great acrobats of the sea, skimming the crests and troughs of the waves with unparallelled agility on tiny, parchment-thin wings, their chocolate brown bodies no bigger than a thumb. Imagine the basilic vein under the wing, like a thread pulled from a blue towel and the smallest vein I have ever sampled.

Imagine the basilic vein under the wing, like a thread pulled from a blue towel and the smallest vein I have ever sampled

The trick is not to use an unwieldy syringe, but to pierce the vein with a fine-gauge needle after plucking a few downy feathers and clarifying the skin with spirit. The resultant bleb of blood is drawn up using the natural suction of a capillary tube.

I then transferred the blood to labelled vials by delicately blowing down the tube, taking great care not to create a bewildering scientific paper by adding my own DNA. The vials contained the best preservative of all: absolute alcohol. That’s 99.8% ethanol, which knocks every fermented beverage known to man into a cocked hat.

Why go to such bother? Because the days of yore when naturalists would run around with nets and guns, bag a specimen, preserve it by drying, stuffing and glueing, measure up its distinguishing characteristics then stick it in a reference collection, have been trounced by DNA analysis. DNA rips away ambiguity.

It deciphers the biological palimpsest and reads the hidden text. There’s a fair chance that the St Helena petrel is a separate species, and that would be a scientific breakthrough. But the debate still rages on.

But the debate still rages on

‘That’s it,’ said Annalee, rummaging in her pack for the radio. ‘I’ll call up the boat then we’ll send off the samples and see if they can make head or tail of them.’ It was our third set, including a previous evening of mist netting when we had collected data from over a hundred birds. ‘Maybe this time we can say whether they are definitively a different species.’

We both accomplished the leap down into the open stern of the boat without too much loss of dignity. Meanwhile Johnny had been fishing and his tub was full of grouper and yellow fin tuna, both excellent eating.

‘Help yourself to dinner,’ he shouted generously over the roar of the engine as he gunned the vessel away from the rocks. But even as he said it, I could see that a speedboat was heading straight for us, and it wasn’t sparing the outboards. At the last moment, as if to avert a collision, it slewed sideways to a perfect halt, raising a curtain of spray. It was the skilful handling of Craig Yon, owner of a local dive business.

‘Joe, you have to come quickly, you have to save my dog. She’s dying. Please, please come now.’ Craig had the unflappable disposition of a marine, but his dogs were his passion.

‘Of course, Craig, or course.’ I clambered across the divide and Craig tore me back along the coast to Jamestown.

Never a dull moment for an island vet.

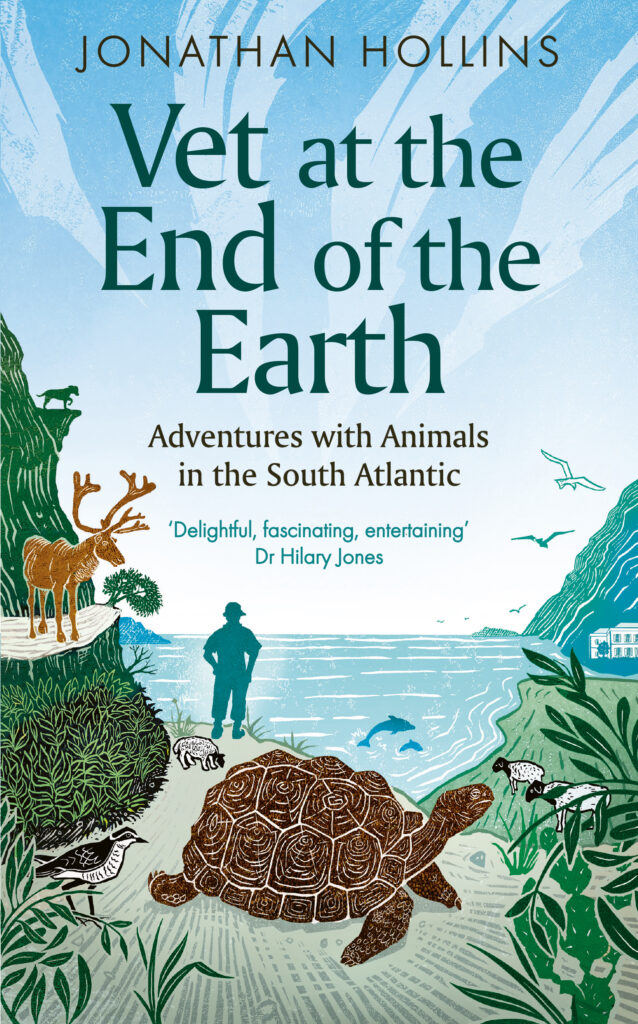

Enjoy more adventures with animals on the South Atlantic Islands

You can enjoy more fascinating tales of island vetting in his hugely entertaining and affectionate memoir, Vet at the End of the Earth – out now.

‘A delightful, fascinating and entertaining book’ – Dr Hilary Jones MBE

The role of resident vet in the British Overseas Territories of the Falklands, St Helena, Tristan da Cunha and Ascension encompasses the complexities of caring for the world’s oldest land animal – a 200-year-old giant tortoise – and MoD mascots at the Falklands airbase; pursuing mystery creatures and invasive microorganisms; relocating herds of reindeer; and rescuing animals in extraordinarily rugged landscapes, from subtropical cloud forests to volcanic cliff faces…