Guest post

Looking At, Looking Down:

Why I Wrote Vagabonds

Vagabonds began with a picture.

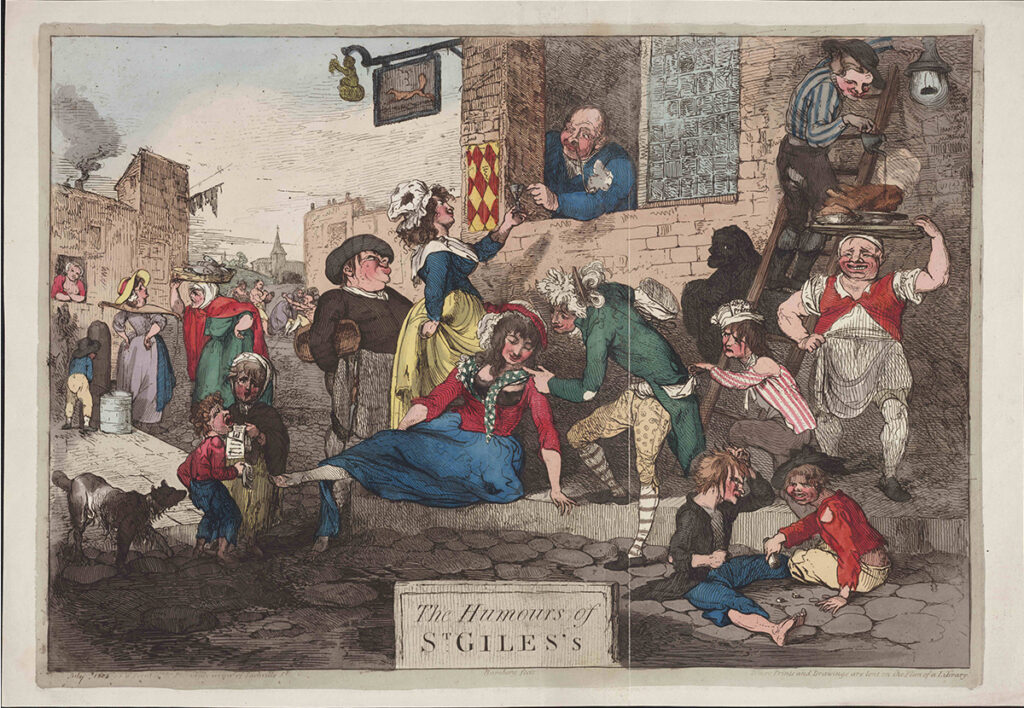

Not of the bun-selling boy on the cover; he came last of all and his gaze will fascinate me forever. But with a very different sort of image – a bright, chaotic, Regency caricature, not the first thing you’d associate with the lived reality of the nineteenth-century street.

The Humours of St. Giles's

The picture in question (Figure 1) is The Humours of St. Giles’s, first published as an engraved print in 1788, and in this coloured edition (below) in 1803, but originally drawn by a man called Johann Heinrich Ramberg.

Ramberg, a young Hanoverian, was a court painter to George III. By birth and by station, he was a stranger twice over to the world he sends up here in riotous Hogarthian style.

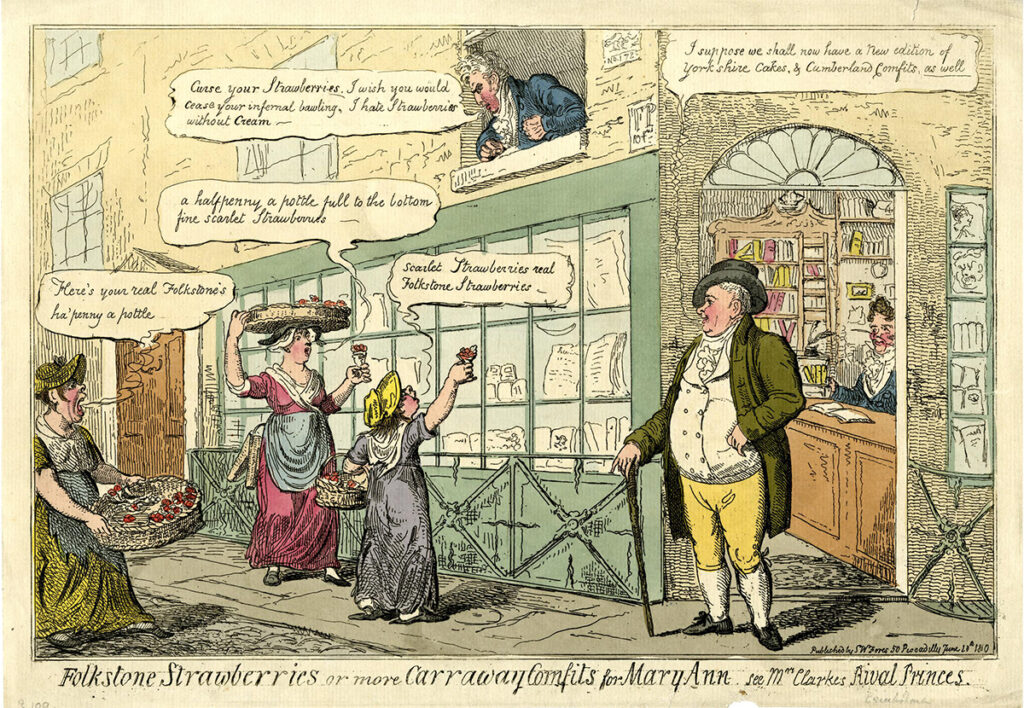

Admittedly, the people responsible for turning his image into a print were a little lower on the social ladder. Thomas Harmer and Samuel William Fores, its first and second publishers, were technically mere tradesmen.

But even their gleaming shopfronts opened on to high-class Piccadilly, a world away from the grubby slum that Ramberg has depicted.

This is why I wanted to write a book about the real people behind pictures like Ramberg’s.

I’ve written Vagabonds almost in opposition to that picture, in a mixed spirit of empathy, frustration, fascination, determined to get past these snooty representations to a world of first-hand experience.

I’ve written Vagabonds almost in opposition to that picture

But perhaps the best way to begin isn’t by throwing The Humours of St. Giles’s aside. Partly because it’s not the sort of thing people did throw aside.

Roughly A3 in size, it was worthy of being pasted on a wall or into an album, and would set you back, for the coloured edition, full two shillings – about two days’ earnings for the street-sellers it mocks.

If we want to empathise with those sellers, we can’t afford to start throwing things away. So instead let’s keep it and look at it once more.

We are in Ramberg’s imagination

The most obvious question to ask of this picture – where are we? – has an equally obvious answer: we are in Ramberg’s imagination.

He has conjured into being a cast of street people taken from life, from stereotype, from other pictures: the boy piddling into the milkmaid’s pail is an irreverent updating of two figures from William Hogarth’s The Enraged Musician. (Figure 3)

Ramberg has arranged them in a made-up street. But it looks like Seven Dials, the geographical and spiritual heart of St Giles’s.

The pub sign might be the Fox, on Castle Street. The church in the background is surely St Giles in the Fields, but Ramberg has taken the ‘fields’ bit rather literally, gesturing towards what remained true at the end of the 1780s – central London was still open to the country, and there really were rolling fields just the other side of the British Museum.

You could traipse them all the way to Somers Town and suburban St Pancras, if you were prepared to trespass and weren’t afraid of cows. We’re in the centre of London’s first slum, but the growing green world is just over there.

We’re in the centre of London’s first slum

It’s plain enough what Ramberg is up to: moral lessons with a wink.

Here are lust and gluttony front and centre, sloth in one corner, wrath and pride in the background. Satire and disorder rule.

The lamplighter’s oil pollutes the cook’s steaming joint just as the boy’s urine pollutes the unattended milk. A pickpocket sports a pamphlet in his cap that proclaims ‘Liberty & Property’. The watching chimney-sweep wears his own shadow.

These are also sins being punished: it’s the bickering milk-maid, the lazy butcher, the lecherous hairdresser, the old man who fancies himself still a bare-knuckle boxer, who get their come-uppance. So there is a moral order in evidence after all, albeit an unforgiving one.

Irishwoman a measure of gin

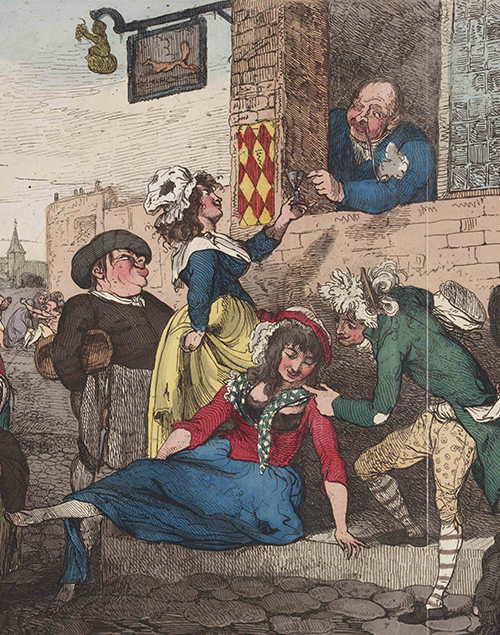

Nowhere is this clearer than in the strong diagonal sweep that gives the picture its shape.

The publican serves a young Irishwoman a measure of gin (see Figure 4). From the leer on the face of the baker at her side, we begin to suspect this might be going somewhere.

It is, says Ramberg, and leads our eye to the quite literally fallen woman, drunk and vulnerable, preyed upon by the lecherous hairdresser.

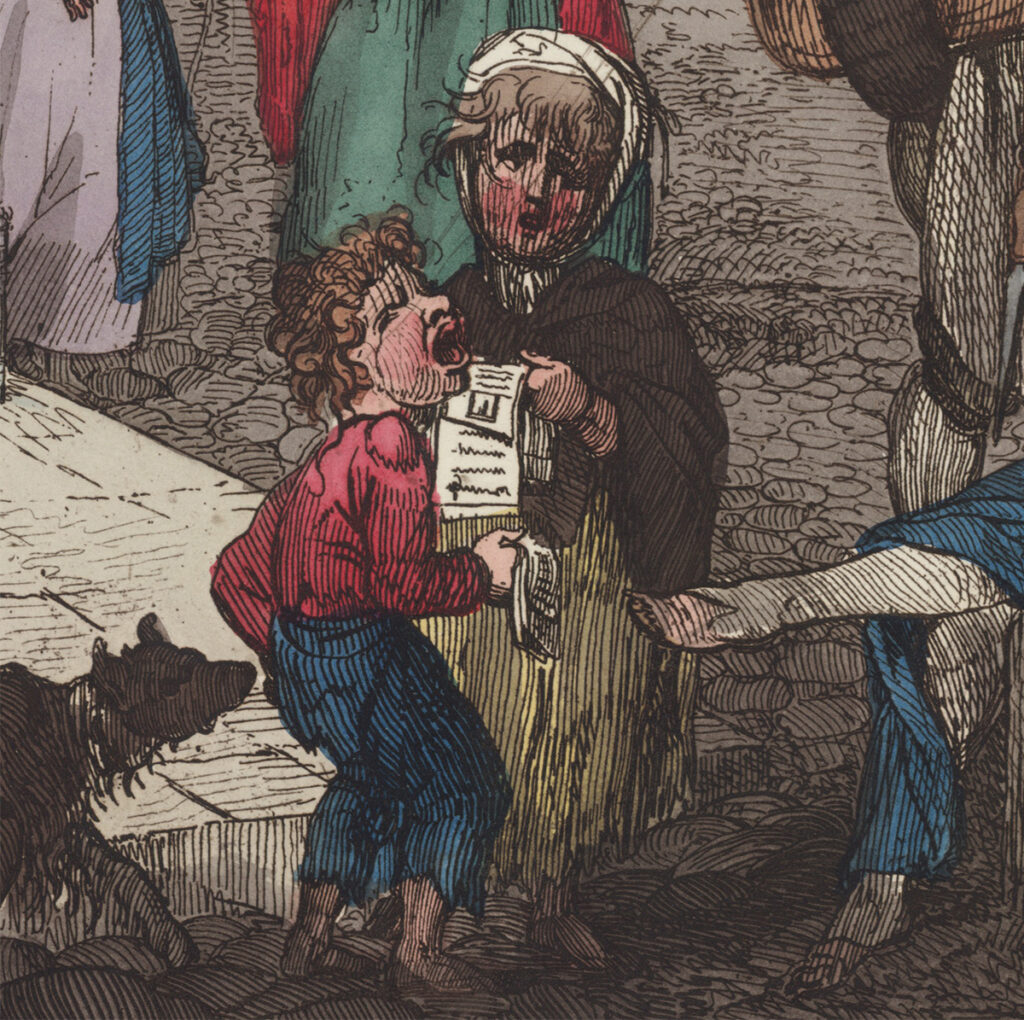

In the original engraving, her breasts are bare – and so are her feet, which point us to the fruits of all this dissolution: two ragged children in the gutter, reduced to ballad-singing in order to survive (Figure 5). The boy, perhaps flea-ridden, scratches his behind as a dog approaches to sniff it – they are, suggests Ramberg, no better than beasts.

Reduced to ballad-singing in order to survive

Here are lust and gluttony front and centre, sloth in one corner, wrath and pride in the background. Satire and disorder rule.

But he has something even worse in his mind. Look closer still, and you can just make out the woodcut illustration on the slip-song that the girl – the young singer we started with – is carrying.

The Humours of St. Giles's

It’s someone being hanged.

For painter, printer, purchaser, it all confirms the received wisdom: this is the underclass, condemned through their own wickedness to the gutter or the gallows. A morbid moral for a ‘humorous’ picture. And a terrible attitude to take towards some of a city’s most interesting and energetic citizens.

Hence Vagabonds – my attempt to do better.

Immerse yourself in the world pictured in The Humours of St. Giles’s by reading Oskar Jensen‘s extraordinary history book, Vagabonds: Life on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century London.

Vagabonds is a compelling, moving and unexpected portraits of London’s poor – the Dickensian city brought to real and vivid life.

A Times Book of the Year

For the first time, this innovative social history brilliantly – and radically – shows us the city’s most compelling period (1780–1870) at street level.

From beggars and thieves to musicians and missionaries, porters and hawkers to sex workers and street criers, Jensen unites a breadth of original research and first-hand accounts to tell their stories in their own words.

What emerges is a buzzing, cosmopolitan world of the working classes, diverse in gender, ethnicity, origin, ability and occupation – a world that challenges and fascinates us still.

Praise for Vagabonds

‘Jensen gives these past lives a monument, a dignity and recognition they deserve. For a brief moment, in the pages of this extraordinary book, they are London and London is them’

Gerard DeGroot, The Times

‘A vigorous and necessary account made timely by the widening chasm between obscene wealth and dire poverty in our contemporary metropolis’

Iain Sinclair, author of The Last London

‘Vagabonds allows readers to feel the injustices and the seeming inevitability of lives going wrong. The writing is compelling, often displaying the flair of a nineteenth-century journalist or courtroom lawyer’

Ana Alicia Garza, TLS

‘Compellingly written, utterly captivating… Jensen’s book is stuffed to bursting with original voices and sources alongside his well-crafted expert analysis… every page of Vagabonds rings with the thrum and bass of a city that saw itself as the centre of the world’

Fern Riddell, BBC History

‘Rich in research… a telling account’

Martin Chilton, Independent