How weeds connect us: a journey through the understorey of time

Author Anna Chapman Parker divulges how a historic painting opened her eyes to the nature all around us and how it shaped her journey towards writing Understorey.

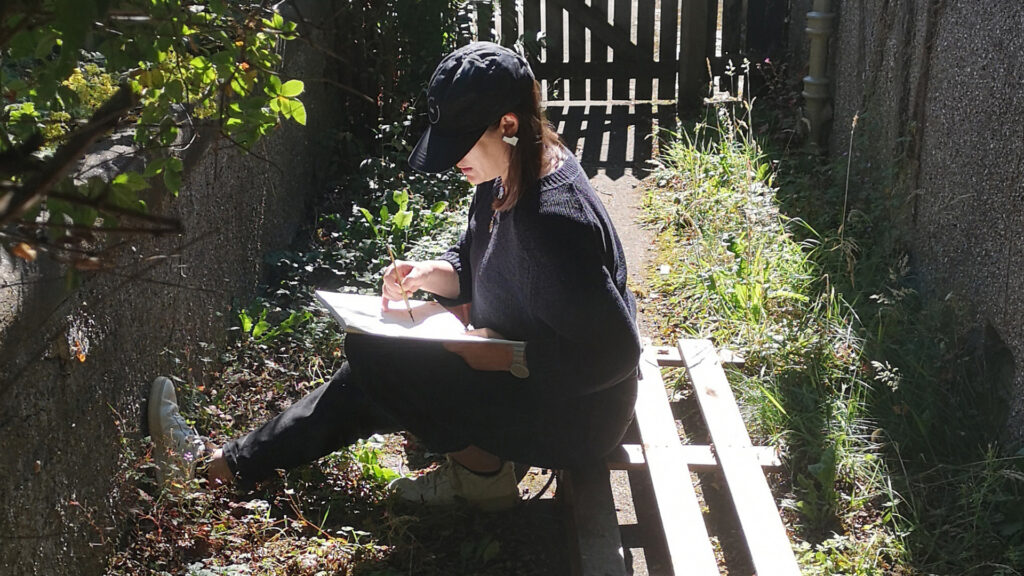

It began as a way of drawing nothing – as near as I could get to that. I always kept a notebook and pen in my bag. My children were very young, I was rarely alone, and I felt an urgent need to find a still and focused space of my own, however briefly.

We’d head out and there would be some hiatus when I wasn’t needed, and I’d grab my chance. No time to think about it or search around for a subject – just drop down and draw whatever was growing through the ground.

The drawings became more sustained as my children grew, sometimes done alone, or with barely a glance at my increasingly independent companions.

It began as a way of drawing nothing – as near as I could get to that

Beyond a vague curiosity, though, the plants still didn’t mean much to me; I recognized few by name, and that was a relief. My lack of knowledge precluded any sense of having to care about them. They were simply something to latch on to, pulling me from myself and out on to the page. My sketchbook became a kind of room of my own, peopled with an assortment of weedy inhabitants I didn’t have to talk to.

The shift began with a six-hundred-year-old bindweed. One day in London I’d wandered into the National Gallery, and, finding myself in the galleries of early Italian paintings – among the glowing, gilded rows, cerulean blue, dark umber, venetian red – I realized I was looking at the ground in the paintings more than at the figures.

My sketchbook became a kind of room of my own, peopled with an assortment of weedy inhabitants I didn’t have to talk to

The plants were everywhere – dotted all over the dry ochre earth, emerging from the cracks in every rock, creeping out, even, from the edges of the picture frames.

Piero della Francesca, The Baptism of Christ, 1437: I didn’t know the story, but here at the protagonists’ feet was a cluster of weeds as intimately familiar as my own hand. They were lightly and deftly drawn, picked out in olive green: grasses, some vague wispy flowers, and the heart-shaped leaves of the bindweed at the end of my own street.

It was this encounter with painted weeds, the same flora I knew, observed half a millennium ago, which marked the beginning of a new way of relating to the plants.

Weeds were no longer accidental green stuff that didn’t matter, they were a living constancy, a kind of wild connective tissue across time and place. I wanted to know them better.

What were these plants that accompany every walk outside, yet pass beneath our notice? When and how did they emerge, flower, subside and disappear through the course of a year? And what constituted a weed, anyway?

Weeds were no longer accidental green stuff that didn’t matter... I wanted to know them better

In answer – I set out very simply to observe and record the plants I found over the course of a year. Along the weed-lined pavements, carpark edges, parks, and roadside verges near my home, I began to draw and write down what I saw.

I live in a small town in the north of England, not a rural idyll; you could find most of the plants I’ve recorded within a short walk of almost any front door.

As I went out and looked at them, the plants linked me to other eyes looking at the same shapes across the centuries, like Piero’s bindweed, illustrations in medieval manuscripts, early photographic experiments, more recent and contemporary artworks too. I included some of these images and observations alongside my own.

You could find most of the plants I’ve recorded within a short walk of almost any front door

I began my year of weeds with the intention of studying plants. But as my notes and drawings accumulated, I realised that as much as I was learning about the plants themselves, I was learning more about how to encounter them; how I might attend to those encounters.

Looking back now at those sixteenth-century weeds in Piero’s painting; I see why the artist might have included them in his narrative. The weeds do more than fill an unused corner of the ground: they cement the figures in a place that’s real, that’s resolutely familiar and connects us all.

Even as we spray our streets with pesticides and concrete over our front gardens, these most resilient and prolific of plants will find a way through the slightest of gaps and might offer us hope.

A beautiful and highly original artist's diary of a year spent observing wild plants

Memoir/Nature/Art

Hardback

Available now

ISBN 9780715655207

‘This tranquil, meditative book is all about the quiet pleasure of examining something closely in order to truly appreciate it’ Daily Mail

In Understorey, artist and writer Anna Chapman Parker records in prose and stunning original line drawings a year spent looking closely at wild plants. Meditating too on how they appear in other artists’ work, from a bramble framing a sixth-century Byzantine manuscript to a kudzu vine installation in modern Berlin, she explores the art of paying attention even to the smallest things.