Guest post

The Celtic Calendar and Irish saints, gods and goddesses of In Ordinary Time

The story of In Ordinary Time is not a linear one. I write about the deaths of my siblings, alcoholism, family mental illness, the Famine, British colonialism in Ireland, the abuses of the Catholic Church and the Irish State. I wanted to show how these traumas manifest in individual lives in the present.

There are three strands in this memoir:

1. the story of my life (1973-present),

2. the history of Ireland,

3. and the pre-historic and mythological stories that have filtered through.

Our understanding of time is fundamental to our understanding of ourselves, and I found Henri Bergson’s concept of la durée to compliment the Celtic wheel of the year.

Here are some of the concepts and characters – the Celtic Calendar and Irish saints, gods and goddesses – that helped bring this story around.

Imbolc

The pre-Celtic feast of Imbolc is celebrated from sundown on February 1 to sundown on February 2 (to include a full rotation of night and day). Imbolc means “in the belly” in recognition, perhaps, of pregnancy in ewes.

February 1 is the first day of Irish Spring.

The Goddess, Brigid

Brigid is the goddess of Imbolc. She is patron of the healing, smith-work and poetic inspiration. A protective mother goddess, she ushers in spring with its all its possibilities, renewals and new life.

St. Brigid

In Ordinary Time begins at St. Brigid’s Church in Manhattan’s East Village. A young Irish woman died an alcoholic death in a church portal on a cold February night in 2011.

An investigation into her life brought me into a confrontation with my own, and with the larger social structures that shaped us both.

As a child, St. Brigid (451 – 525CE) was fostered out to a Druid to be educated. Later, she converted to Christianity and became a nun. She started Ireland’s first Convent and art school. Writing about her in the middle ages, Christian monks superimposed stories of her life over those of the Goddess Brigid. These were used as teaching tools to convert a deeply pagan people.

However, St. Brigid retains much of the pre-Christian spirit, and Irish people, particularly women, carried her stories with them when they emigrated around the world.

St. Brigid’s Feast Day coincides with Imbolc. It can be celebrated on February 1st or 2nd.

1 February 2023 will be the first state recognized St. Brigid’s Day, and the first Irish holiday named for a woman. The publication of In Ordinary Time on 2 February will coincide with this celebration.

St. Patrick

St. Patrick is Ireland’s patron saint. He is recognized for bringing Christianity to Ireland.

His feast day is March 17 which coincides, approximately, with the spring equinox, which falls half way between Imbolc and Bealtaine.

When I was growing up in Ireland in the 1970s and 80s, approximately 90 percent of Catholics attended Sunday Mass on a regular basis. St. Patrick’s Day was a holy day of obligation.

The name Patrick is of Latin origin, Patricius meaning “father” or “nobleman.” The patriarchal name helped me understand the hold the Catholic Church had over the forming psyches of generations of Irish people.

Bealtaine

Bealtaine is celebrated on May 1. It is the first day of Irish summer, a time for youth, fertility and finding love.

I identify this time with emigrating, a young working-class woman leaving an oppressive Ireland for the freedom and adventure of life in New York. It is a time of new friendships, of falling in love and trying to find a creative voice. It was during this period of partying that my adventures in alcoholism commenced.

The summer solstice occurs during the season of Bealtaine. “Solstice” means “sun stands still.” On this day, June 21, it appears the sun stalls momentarily in the sky, before pitching us toward the darkening half of the year.

My brother died in a motorcycle accident on the summer solstice in 1998. This event felt like a rupture in time. The world before, and the world after Peter died.

Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh is a harvest feast. It is celebrated on August 1st, the beginning of Irish Autumn.

It falls mid-way between the Summer Solstice and the Autumn equinox.

The God, Lugh

Lugh (for whom Lughnasadh is named) is a harvest God. His name evokes a promise, that what was sown will be reaped.

I think of the fragments of my family history from Famine times to the present, our struggles with alcohol through the generations, and how all the buried, forgotten and dismissed parts of ourselves find a way to surface.

The Autumn Equinox

The autumnal equinox falls mid-way between Lughnasadh and Samhain. It marks the day when daylight and night are of equal length.

It was during this time that the story of coming to sobriety found a way to be told.

at Autumn Equinox

Samhain

The feast of Samhain is celebrated on the eve of October 31 to the eve of November 1.

It has evolved into Halloween, but it was once Celtic New Year. The Celts celebrated the start of the day at dusk and the start of the year going into the dark months. They understood that darkness is as necessary as light for harmony and growth.

On the eve of Samhain, the veil between this world and the Celtic Other World, inhabited by the departed and other beings, is so close that it is possible for us to cross back and forth.

It is a time to reconnect with our ancestors, and to remember that our beloved dead are always beside us.

In this dark time of the year, I thought about the dark moments in history, like when, in the mid-nineteenth century, Irish immigrant women were used for medical experimentation in New York hospitals.

In the present, there was the dark period of my brother’s mental health crisis, and my own ongoing struggle to accept the cloud of chronic migraine that blots out days of my life every month.

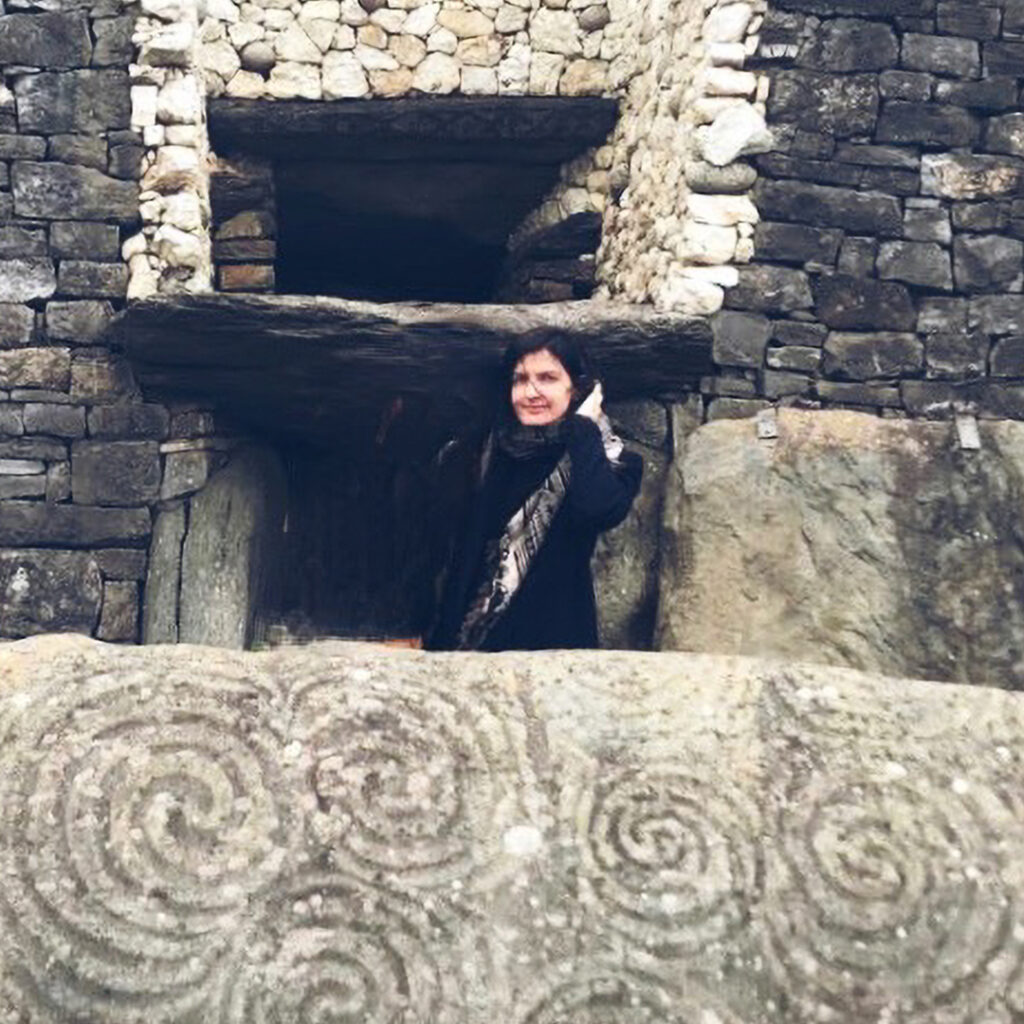

The Winter Solstice

The Winter Solstice occurs around December 21. It was a vital celebration for the agrarian, ancient peoples of Ireland.

Monuments like the five-thousand-year-old Newgrange celebrate this time.

It marks the turn from darkness to light, and those first few rays of morning sun that will continue to rise earlier and earlier in the coming months.

monument, Co. Meath

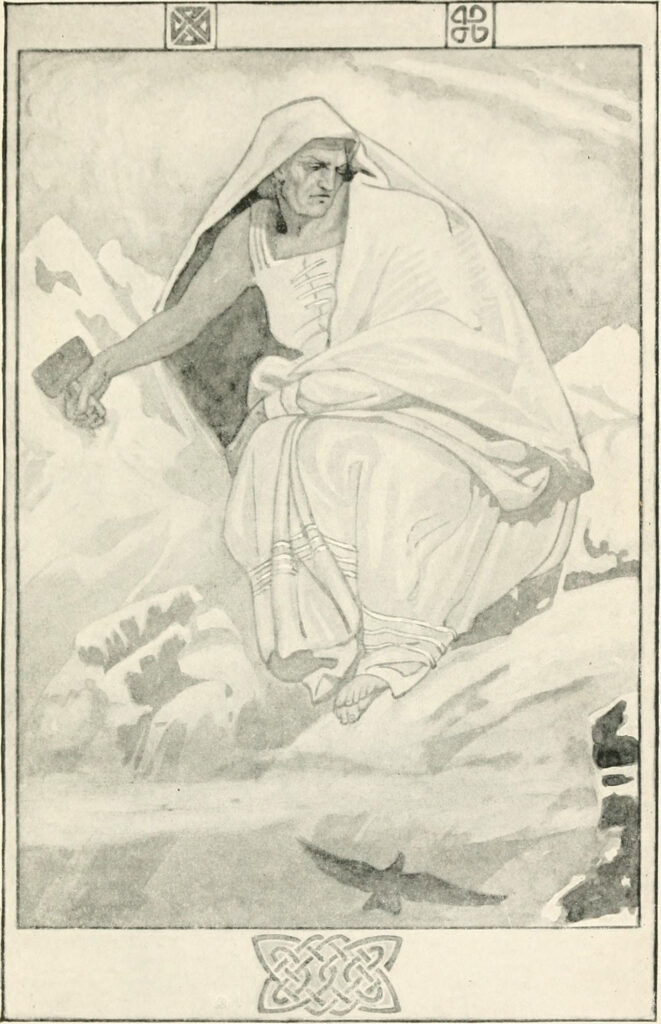

The Cailleach

It was in the darkness that I encountered the Cailleach, the wise old woman of winter.

She is a creator goddess and it was in her time that I moved home to Ireland, to the rugged landscape she carved out of Ireland’s West coast.

She helped me to understand the cyclical rather than the linear nature of time.

and Legend (1917)

She tries to prolong winter as long as she can, but there comes a morning where she just stays in bed, and as she drifts back into sleep, she lets go, little by little, and when she does, the ground softens, Brigid returns, and another new season begins.

If you enjoyed Carmel Mc Mahon‘s article about the Celtic Calendar and Irish saints, gods and goddesses you should try reading In Ordinary Time: Fragments of a Family History.

Mc Mahon’s powerful memoir is a multi-layered exploration of trauma, time, memory, grief and addiction that draws connections to the events and rhythms of Ireland’s long Celtic, early Christian and Catholic history.

In 1993, aged twenty, Carmel Mc Mahon left Ireland for New York, carrying $500, two suitcases and a ton of unseen baggage. It took years, and a bitter struggle with alcohol addiction, to unpick the intricate traumas of her past and present.

From tragically lost siblings to the broader social scars of the Famine and the Magdalene Laundries, In Ordinary Time mines the ways that trauma reverberates through time and through individual lives, drawing connections to the events and rhythms of Ireland’s long history.

Praise for In Ordinary Time

‘A vivid, evocative and resonant counterpoint of time, memory and meaning’

Joseph O’Connor, award-winning author of Shadowyplay

‘Stunning. A work of great emotional and intellectual heft, about how familial trauma and the collective past suffering of a nation can engender the nameless psychic pain of the individual. Truth and honesty shine out of every line’

Mary Costello, author of Academy Street

‘Beautiful, compelling, thought-provoking… Mc Mahon draws us a kind of map for our broken hearts… An uncompromising reflection on what it means to be of Irish heritage today’

Tara Flynn, author, actor and broadcaster

‘In Ordinary Time is painfully familiar in its account of family loss and trauma in the urban working class… Sensitively written and quietly devastating, it’s the book I had been waiting for — the darker shadow twin of Marian Keyes’

Niamh Campbell, award-winning author of This Happy

‘Magnificent. In Ordinary Time is a brilliant combination of the personal and impersonal, of the collapsing of the two worlds one into the other. Spare, pristine, bracing – a marvellous book’

Carlo Gébler, author of Confessions of a Catastrophist