‘The blade must woo the wood’: Jenny Uglow reflects on the work of David Esterly

To meet the resurgent interest in wood arts and craft, this month, we republished The Lost Carving, an inspiring reflection on creativity and mastery by world-renowned artisan David Esterly.

Jenny Uglow, highly acclaimed critic, biographer and author of numerous prize-winning nonfiction books – including The Lunar Men and Nature’s Engraver – contributed a new and rousing introduction to this beautifully repackaged memoir.

By Jenny Uglow

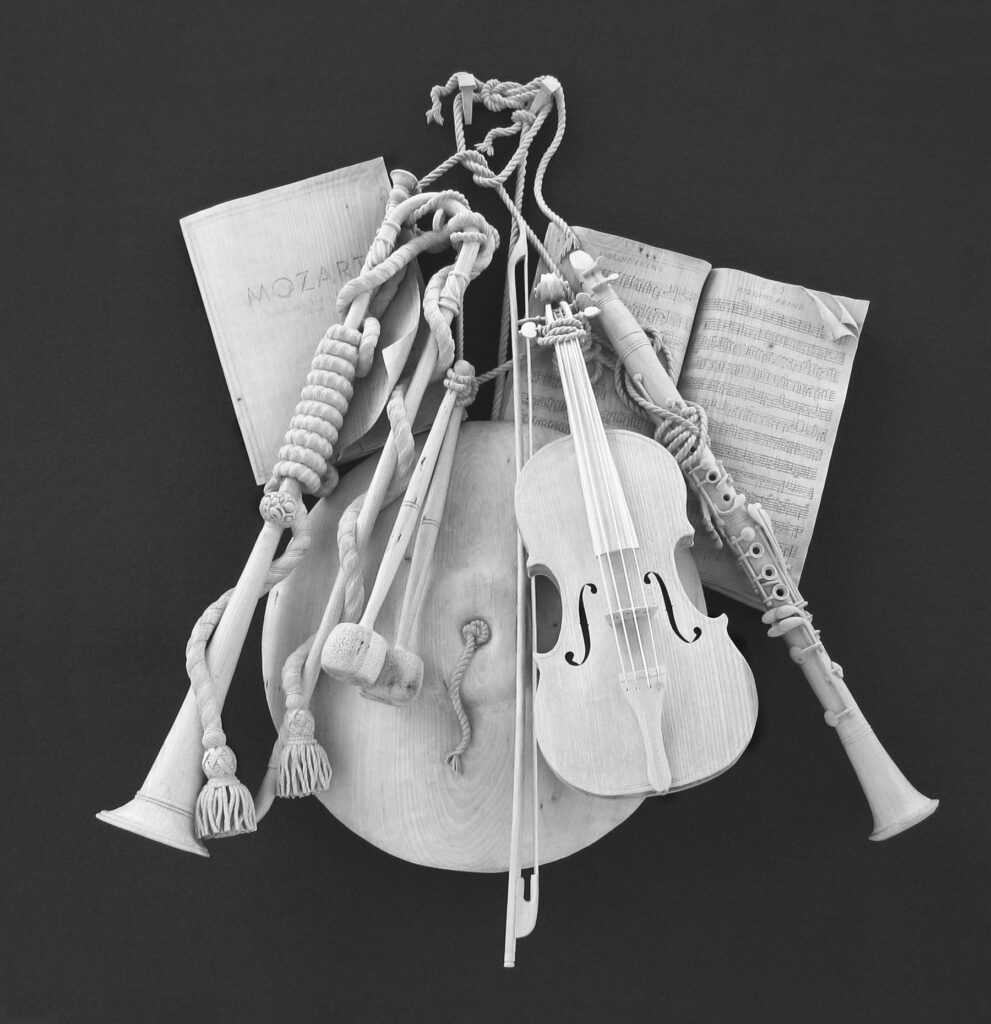

From the first page, as David Esterly whisks us into his studio, this is a magical book, transporting us to a woodcarver’s world. We breathe in the nutty scent of limewood shavings and see the tools laid out on the bench, 130 chisels and gouges each with their own role, their own history. He reaches instinctively for the one he needs. With a ‘little gunslinger’s twirl’, he floats the handle into his palm, poised to shape the petal of an iris, the curve of a violin, the swell of a peach.

Esterly, who died in 2019, was a master of his art but also a captivating storyteller. Three narratives run through this memoir, their turns and returns appearing as effortless as his intricate carvings.

In the foreground, as the seasons change around his studio in the foothills of the Adirondacks, he works on different carvings and writes this book. In the background runs the story of his first sighting of Grinling Gibbons’s miraculous swags of fruit and flowers in St James’s Church, Piccadilly, many years before:

‘It seemed one of the wonders of the world. The traffic noise on Piccadilly went silent, and I was at the still center of the universe.’

It is a bodily apprehension, a tingling in the palms of the hands, beyond words.

Abandoning Cambridge and academia, he decides to write about Gibbons. But that is not enough. He must learn to carve. We follow his struggles to emulate Gibbons’s lost art, living deep in the Sussex countryside. Beside him, his wife Marietta restores old porcelain, another patient recoverer of past skills.

Hovering behind his labours is Gibbons himself, the young Dutch carver spotted by John Evelyn through a Deptford window in 1671.

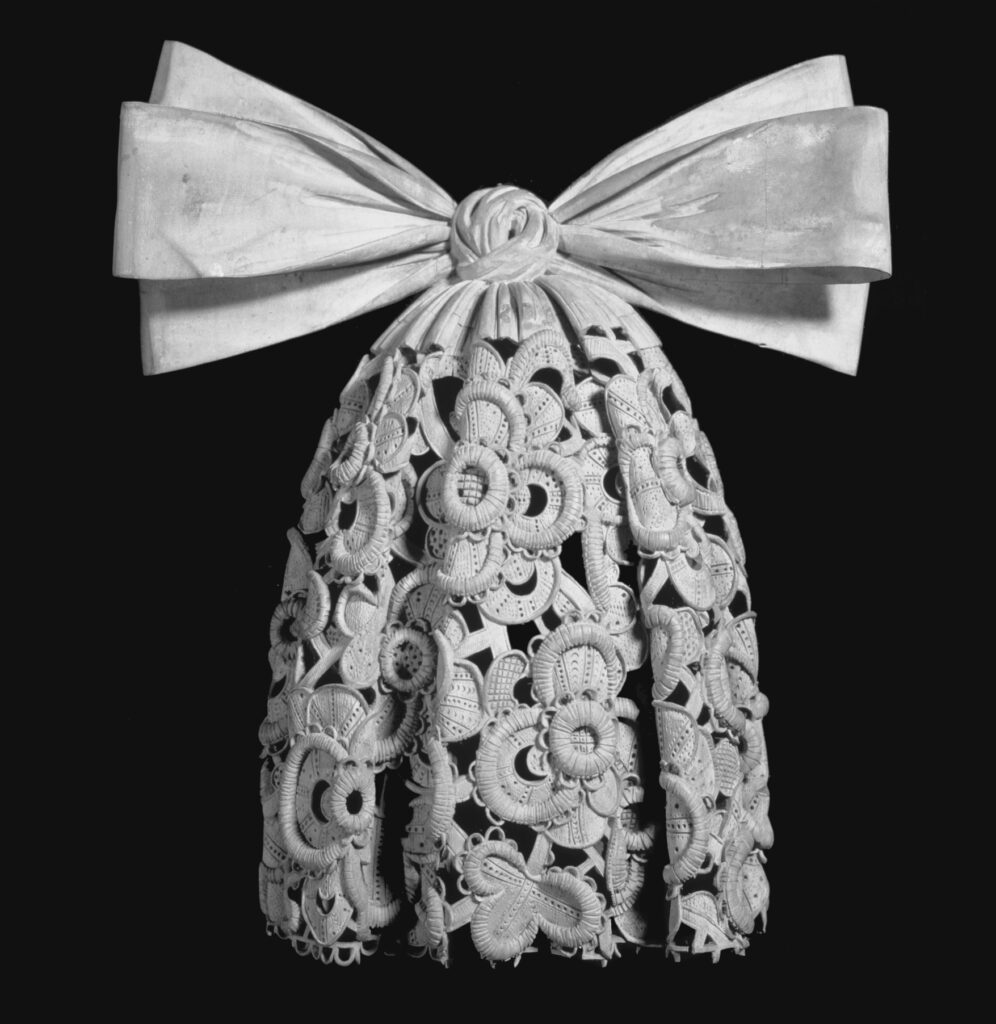

We think of wood as brown, but Gibbons worked in the European tradition, using limewood, ‘the palest wood in the forest’, a contrast to English oak, so that his decorative swags ‘floated ghostlike over the darker […] paneling’.

Over the years – while becoming known as a Gibbons expert – Esterly finds it increasingly hard to shake off the ghostly presence that whispers on his shoulder and jeers at his efforts.

His release comes in the central story, the core of the book. On Easter Monday, 31 March 1986, he hears on the radio that the upper floor of Hampton Court Palace is on fire.

Flames funnel through the King’s Apartments, built by Christopher Wren for William III, and although paintings are hustled to safety, Gibbons’s elaborate overmantels and drops blacken in the smoke.

After frustrating arguments as to whether only a British carver should be appointed, Esterly is called in. His task is to provide the brief for the restoration and to recreate the only carving lost, it seems, beyond hope: a complex seven-foot-long drop framing a door, now burnt to a shapeless lump.

The start is unpromising. Fingering a delicate stem, he hears a quiet, sickening snap – a small break, easily glued, but the first of many hard lessons from the wood.

Once the carvings are off the wall, he studies them carefully, noting the acute angles, the careful layering, the dangerous thinness. He sees too that copying is not enough. An accurate copy of a leaf turns out oddly lifeless: only the subtle exaggeration that ‘translates’ it into art can capture the essence of the living form.

In Grinling Gibbons and the Art of Carving, written to accompany the exhibition that he curated at the V&A in 1998, Esterly quotes Horace Walpole’s assertion that no one before Gibbons ‘gave to wood the loose and airy lightness of flowers, and chained together the various productions of the elements with a free disorder natural to each species’.

That airy quality also describes his own curling and entwining scenes, translating his art into words. But at every stage you feel, too, a driving force, an incisive energy, clear and sharp as the woodsman’s axe: he reminds us that the grace of a limewood swag begins in violence, the ruthless ‘killing and dismemberment’ of a fine tree.

An inner drive powers him, whether carving at his bench, walking on the Sussex downs, skiing under a full moon, kayaking against a fast-flowing current. Rivers flow through the book, from the still Cam and the wide Thames to the river outside his studio in upstate New York, as it surges in release from the ice.

As readers, we are given a rare insight into the tension between momentum and control that informs the carver’s craft from the moment he picks up his tool.

An assault will not work; ‘The blade must woo the wood.’ One hand curves round the handle, pushing it forward, another rests on the blade, restraining the drive, while the heel of the rear hand rests on the wood, grounding it, keeping it stable. The whole body is involved, even in the bend of the shoulders and twist of the torso. This dynamic balance expresses a deeper opposition of desire and restraint: as Yeats writes, out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry.

One pleasure of this memoir is its exploration of creativity, carrying us to the point when the carver no longer imposes the design but becomes a servant of the carving itself. ‘You work in the churn of the moment, and the forms seem to determine their own shape. You think with your hands. The carving thinks with your hands.’

Recognising that this sense of surrender and oneness is shared by many makers – potters and poets, carvers and composers – Esterly turns to the writers and thinkers he admires. He quotes Yeats’s question, ‘How can we know the dancer from the dance?’

He thinks of the Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus, whose urge to abandon the body and progress to ‘a mode of perception in which seeing and being and creating are one’, is, paradoxically, expressed in a wealth of sensual imagery. He evokes the feelings of ‘oceanic oneness’ in William Blake and Thomas Traherne: ‘You never enjoy the world aright,’ Traherne says, ‘till the sea itself floweth in your veins.’

At moments of high intensity, Esterly tells us, time evaporates. But one of my favourite moments when time folds back upon itself is not intense at all. Esterly and his fellow carver Trevor Ellis are sighing over the never-ending cutting of forget-me-nots.

Poring over the little hole in the middle of the flower with a torch, Esterly sees marks suggesting that the original carver had worked in precisely the same way as they were doing. Then, ‘Look at this,’ says Trevor, producing a tiny plug of wood, which had lain at the bottom of one hole since the seventeenth century.

It is exactly like those they produce themselves. ‘Forget-me-not,’ it says.

This extract is taken from The Lost Carving: A Journey to the Heart of Making (Duckworth, 2024) by David Esterly, introduced by Jenny Uglow.

An inspiring reflection on creativity and mastery by a world-renowned artisan

‘A wonderful, riveting book’ – Edmund de Wall

The highly acclaimed memoir of a renowned artisan with a new introduction by Jenny Uglow, The Lost Carving reveals the inspirational secrets of wood and craft. On a chance visit to St James’s church, Piccadilly, David Esterly was awestruck by the delicate beauty and ambition of master carver Grinling Gibbons’s limewood decorations. The encounter changed the course of Esterly’s life as he devoted himself to these lost techniques.

By 1986, when a fire at Hampton Court Palace destroyed much of Gibbons’s masterpiece, Esterly was the only candidate to restore his idol’s work to glory, though the experience forced him to question his abilities and delve deeply into the subtle skills of making.