Losing my mother tongue

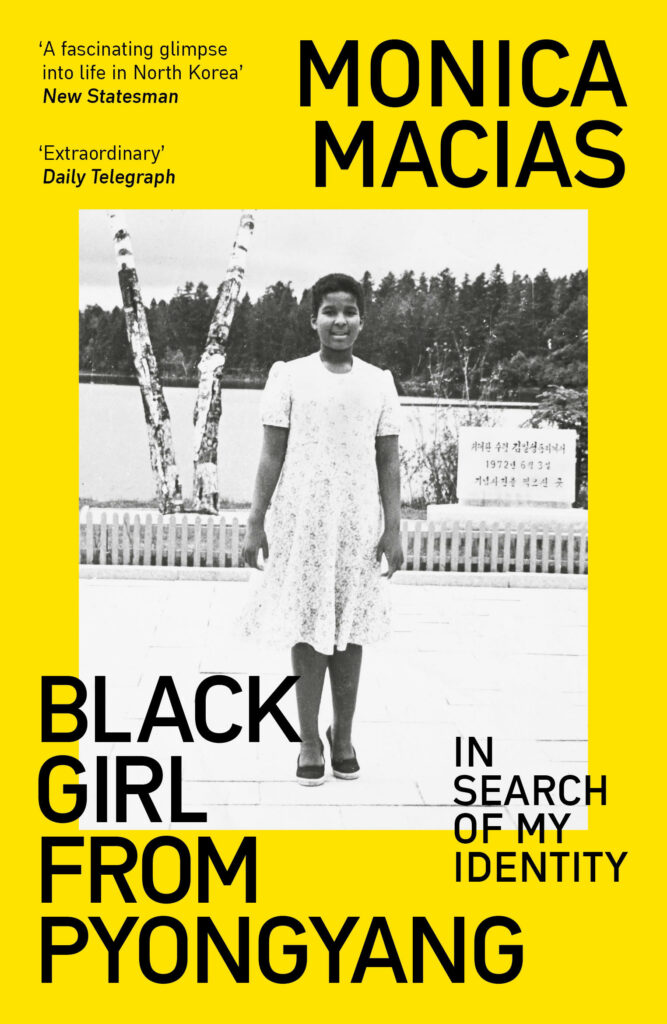

In 1979, aged seven, Monica Macias was sent from West Africa to the unfamiliar surroundings of North Korea by her father, the President of Equatorial Guinea, to be educated under the guardianship of his ally, Kim Il Sung.

Within months, her father was executed in a military coup; her mother became unreachable. Monica would have to make her life in Pyongyang.

In this moving and open piece, the author of Black Girl from Pyongyang reflects on her experiences with pain, strength, and mother-daughter relationships.

“Mother was comfort. Mother was home. A girl who lost her mother was suddenly a tiny boat on an angry ocean. Some boats eventually floated ashore. And some boats, like me, seemed to float farther and farther from land.”

This is a quote from Ruta Sepetys’ novel Salt to the Sea. For me, it evokes my own mother, and how I felt when she left me and my two siblings in North Korea in the wake of my father’s death. Today, I want to talk about pain, strength, and mother-daughter relationships.

My name is Monica Macias. I was born in Equatorial Guinea in West Africa as the youngest daughter of Francisco Macias, the first legitimate president of independent Guinea after it gained freedom from its Spanish colonisers in the late 1960s.

But from the age of seven, I was raised in Pyongyang by the former president of North Korea, Kim Il Sung. Ever since I can remember, my life has been defined by these larger-than-life figures and the absence of my mother all those years ago.

During Guinea’s post-independence period, my father was cautious to align our country with former colonial powers. When communist countries came to us with the promise to invest in our country, my father saw an opportunity to help rebuild Guinea and create new global allies in the process.

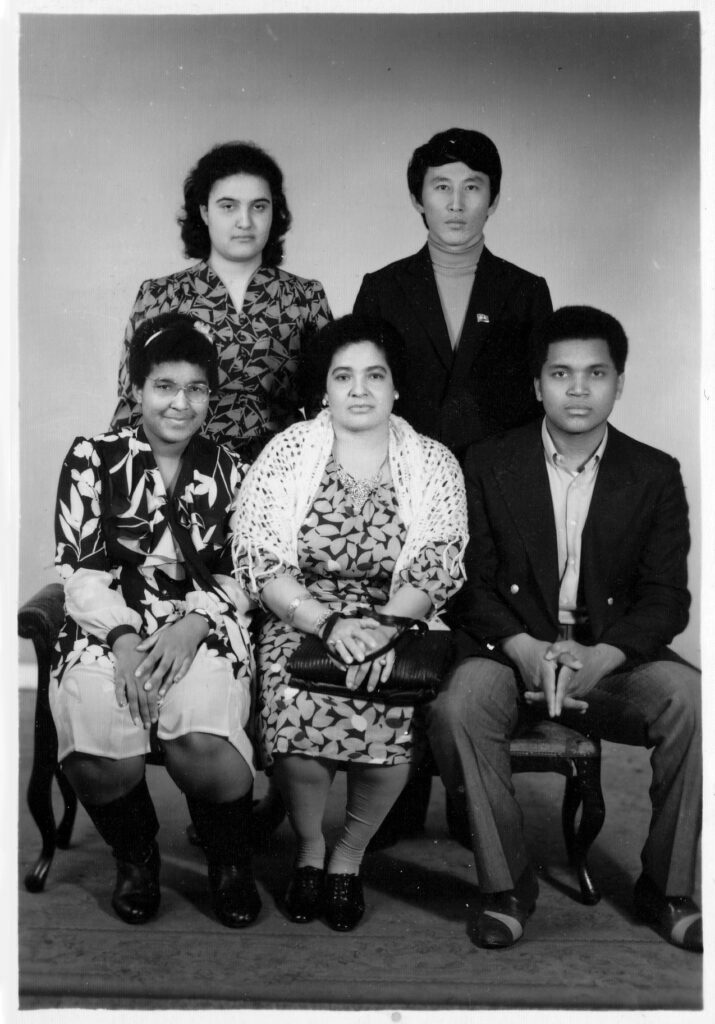

My siblings, Maribel and Fran, and I were sent to study in North Korea. At the time North Korea had a rapidly developing economy and a flourishing education system.

My mother accompanied us to help us settle into our new lives and, taking advantage of North Korea’s well-developed health provision, to get a much-needed surgery. We were given a spacious apartment and quickly adopted the rhythms of our fellow Pyongyang citizens. While my mother recovered from surgery, we spent weekends at parks and amusements alongside all the other families.

The streets thronged with people eating jellyfish barbecue and kimbap followed by fresh watermelon, apples and pears. The scent of the barbecuing beef made my mouth water. The adults drank Soju (a potato-based alcohol similar to vodka) and Taedonggang, North Korea’s most popular beer. When the alcohol took effect, they started playing guitars, singing songs and dancing.

With the four of us together, I was happy. Then quite suddenly, my mother announced, without explanation, that she had to return to Equatorial Guinea. Just like that she disappeared from life. My boat was cast adrift.

Years later, I would learn that not long after we moved to Pyongyang there was a coup d’état in Guinea, launched by my cousin, Teodoro Obiang. He remains in power to this day. My father was captured by militant forces and in a kangaroo court was tried and murdered by the newly formed government.

At the time, my eldest brother Teo was studying in Cuba. In the wake of the uprising in Guinea, he was deported home. With no one else there to serve as his protector, my mother was compelled to return to Guinea and the perils that awaited them both.

But as a child, I knew nothing of these events and every night I spent hours awake in bed, drowning in a sea of tears. I yearned for my mother. In my anguish I refused to eat. For a month nothing passed my lips but water. My weight plummeted and I was taken to hospital, where I was put on a glucose drip that kept me alive.

A month later, when I had physically recovered, I was sent back to boarding school. My classmates were relieved to see me return. Some of the barriers between us dissolved. Special food that I liked was couriered from a hotel in central Pyongyang to ensure that I ate.

From that point on, my attitude changed. I hardened from a natural ebullience into overt rebellion against authority and hierarchy. The loneliness, the frustration and the resignation drove me to reject everything related to my mother – I wanted nothing to do with memories of my homeland.

In contrast to the Korean-born children of my age, I was too tall, my skin was too dark, my hair was too curly. They touched my African hair and gave me the nickname ‘Sheep Wife’ based on a popular cartoon character.

Having abandoned my roots, I wanted desperately to fit in – to be Korean. I refused to speak Spanish, the colonial language of Equatorial Guinea and still its main official language. Even when I was assigned a Spanish teacher, I made his life impossible. He laboured on for three months before resigning, reporting that I was capable but had no desire to reconnect with Guinea.

Before I knew it, three years had passed. One day while we were messing about on the riverbank, my sister, Maribel, came running up to me and told me to dress nicely as we were going to the airport. ‘Mum’s coming. We have to meet her,’ she said.

Since my mother had left us, she had become vaguer and vaguer in my memory. She felt less like a physical person and more like an ethereal being who did not actually exist. I told Maribel that I couldn’t remember our mother. My sister pulled out a photo from her purse and handed it to me. It showed the two of them together. For the first time in years, I stared at my mother’s face trying to recall her.

That afternoon, when we met our mother at Sunan airport, all I could think was, ‘She’s a very pretty lady.’Maribel and Fran swarmed to her side, hugging her tightly and chattering excitedly in Spanish.

But I wasn’t moved to join them. I stood apart with a blank expression. My eyes met my mother’s, then she flung her arms wide and gestured for me to come to her. I approached her hesitantly, before she clutched me to her bosom and cried. Then she started speaking to me, but I couldn’t understand anything she was saying. It had been too long since I had spoken Spanish and I’d forgotten it all.

I kept mumbling in Korean, ‘Mum, I can’t speak Spanish. I don’t know what you’re saying,’ but she couldn’t understand me either. Her smile faded and she muttered something sadly. I asked Maribel to interpret. ‘She thinks you’re not speaking Spanish because you resent her,’ she said.

‘That’s not true!’ I cried. ‘Maribel, you know that’s not true!’ I felt misjudged and disheartened at the same time.

During the time I spent with our mother, I could not hold a proper conversation with her without one of my siblings acting as the interpreter. When the two of us happened to be alone, we had to spend that time in uncomfortable silence.

We all know the term ‘mother tongue’ but this expression doesn’t speak to me. I didn’t know my mother’s language, and my mother didn’t know mine. Mother and daughter were finally reunited but might as well have been oceans apart. The sadness in my heart only grew deeper.

After a few months, Mum returned to Guinea. On the day she departed, I could only offer her a silent embrace.

I remained in Pyongyang until I completed my university studies.

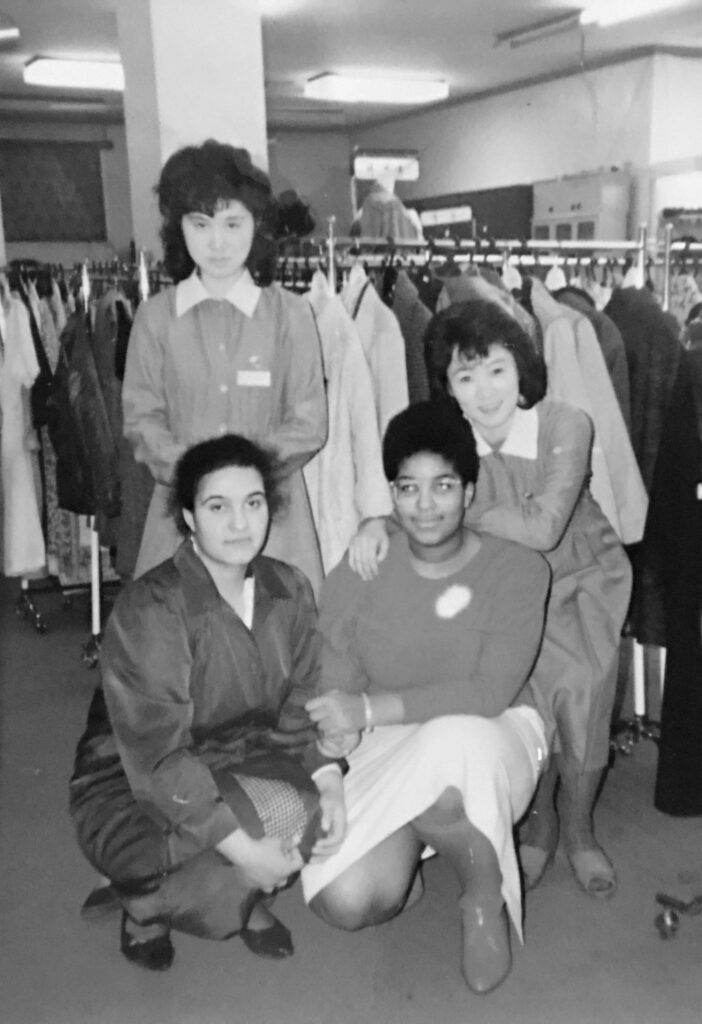

At university, I met students from across the Globe and hearing about their experiences, I began to realise there was more to the world than I had been taught. I had grown up in a sheltered society with little exchange with the outside world. Now I wanted to discover it for myself and who I was within it. Was there someplace where a black girl with a Korean soul belonged? My curiosity led me to travel and meet people from different cultures and to better understand how they lived.

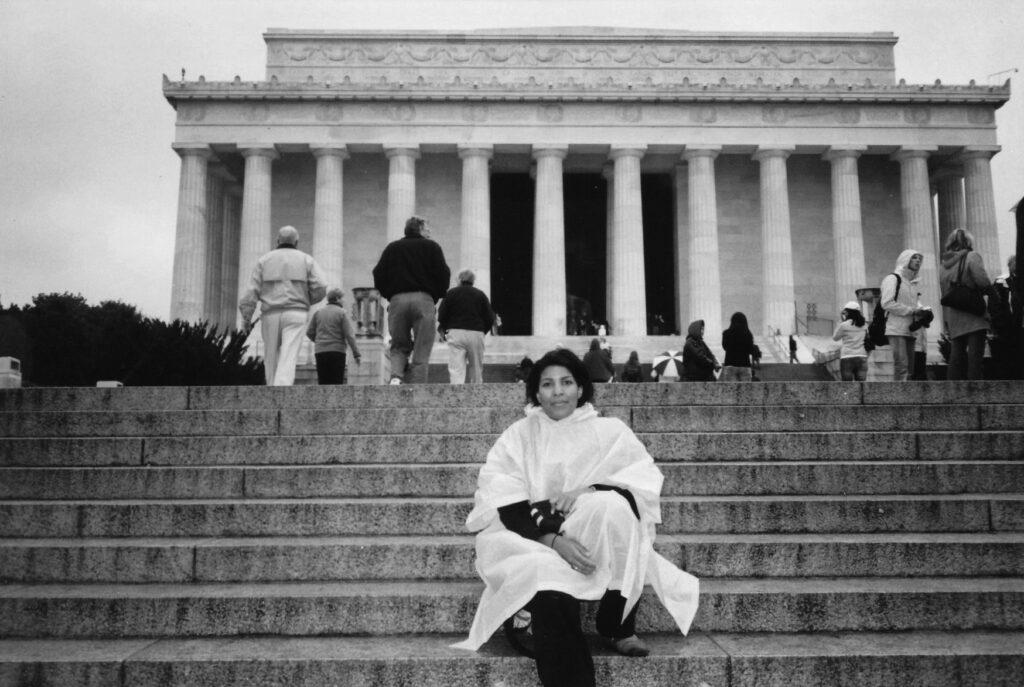

Learning about different societies and considering how politics had defined so much of my life, I became interested in international relations. After considering various options, I decided to take an MA in International Relations in London because it was relatively close to Madrid, where I still have friends and family, and because it is home to some of the best universities in the world.

Growing up in Pyongyang, I had always been noticeably different, despite my efforts to blend in. But in London, I felt marvellously inconspicuous. Still, through all those mostly happy early years in London, studying and working and making a new place for myself, there was a nagging unresolved sadness and sense of longing that was to do with my mother.

It would take many years before I felt ready to sit down with my mother to talk through those lost years and attempt to unpack our shared trauma.

As you can imagine, when we finally broached the subject, we were entering uncharted waters. She accused me of hating her for abandoning me. She had been faced with an impossible decision, leaving some of her children behind to save another one in danger. How could I understand? I wasn’t a mother.

Looking back, I understood that my mother had been through a physically and psychologically painful experience. She had lost her husband, her eldest child was in peril, she was penniless. On returning to Guinea, she suffered physical abuse – even having her leg broken – at the hands of members of my father’s family who had never accepted her.

As difficult as it had been to come to terms with her decision, I had made my peace with history. But still, I wanted her to see things from my perspective. I insisted that she must understand what I had suffered because of her choices. The night ended with me storming away. She begged me to stay but I left anyway, slamming the door on my way out.

A few weeks later, back in London, I received a message from my niece in the middle of the day. ‘Aunty, Grandma is not OK’ it read. I replied ‘You know Grandma sometimes exaggerates, looking for attention. Just hug her and she will calm down.’ As it turned out, my mother had complained to the neighbours of feeling unwell. When they went over to check on her she wouldn’t answer the door. The police found her on the floor unconscious. She would remain in a coma for six weeks before passing away.

At her funeral back in Guinea, I was flooded with contradictory emotions – too many to hope to process. We had had a very complicated relationship. We both wanted love and reconciliation, but our cultures, generational difference and personalities were like oil and water.

Unlike the solemn processions I was raised with in North Korea, Guinean funerals feature singing and dancing. The idea is to let the late person’s spirit go with joy and good wishes.

But it was difficult to celebrate her life with everyone. An image of the last time I saw her, with tears in her eyes, was burned into my memory. Our last conversation had been an argument and I had never told her how much I loved her.

Through all those weeks, I had difficulty concentrating and suffered from insomnia. Maribel – who in many ways had become a second mother to me over the years – persuaded me to see a counsellor. She said counselling could help me to address my problems at their root: the trauma I had experienced as a young girl and that I still carried, as well as the painful relationship with my mother and the guilt I felt over our last heated exchange.

I always thought that I was strong enough to overcome all the difficulties that life had presented me with; that life itself was the best teacher and I, the star pupil. For me, the best therapy was sharing my experiences with the friends who knew me best, not an unknown psychotherapist.

I cried the entire first session. I had never cried like that before; tears fell like a waterfall, leaving me short of breath. It was as if I had a wellspring inside of me and the counsellor had turned on the tap.

In only a few sessions, I started to feel better. It was not that all my pain disappeared with counselling; that pain will be with me forever. Instead, what I learned was to understand, to be aware of the pain and the emotion, and not to ignore them.

I also learned to forgive and make peace. Anger is not a good feeling to carry, especially when we cannot know when the person at whom the anger is directed will depart this life.

Therapy helped me to appreciate how not dealing with my feelings and traumas only negatively impacted the quality of my life. Years of abandonment and military school had convinced me to control my feelings. I still struggle with recognising that we are all vulnerable in the face of life’s difficulties.

If there is any one lesson to be learned from my story it’s that we may be able to draw on deep wells of strength and resilience to meet life’s many challenges, but what is certain is that we cannot face them alone.

We need help to come ashore. I wish I had spent more time working through my feelings and reconciling with my mother before she passed, and I will always regret how much of our lives were spent apart.

When I think of her now, I see a woman who navigated so many storms and still she persevered with a strong sense of character and love in her heart. She wasn’t always perfect, but I’m inspired to be a little more like her every day.

If you still have your mother or another parent or relative whom you cherish, can I suggest that you do one thing: call that person, and tell them that you love them.

This article is an adaptation of a speech Monica gave at the Women of the World Festival, 10 – 12 March 2023 at the Southbank Centre.

The extraordinary story of a West African girl’s upbringing in North Korea

‘A fascinating account of a woman’s quest for autonomy’ – Lily Dunn, author of Sins of My Father

In 1979, seven-year-old Monica was sent by her father, the president of Equatorial Guinea, to be educated under the guardianship of his ally, Kim Il Sung. Within months, her father was executed in a military coup. Monica would have to make her life in Pyongyang. Reaching adulthood, she spent time in Madrid, Malabo, then New York, Seoul and London, in search of her roots.

Optimistic yet unflinching, Monica’s astonishing story challenges us to see the world through different eyes.