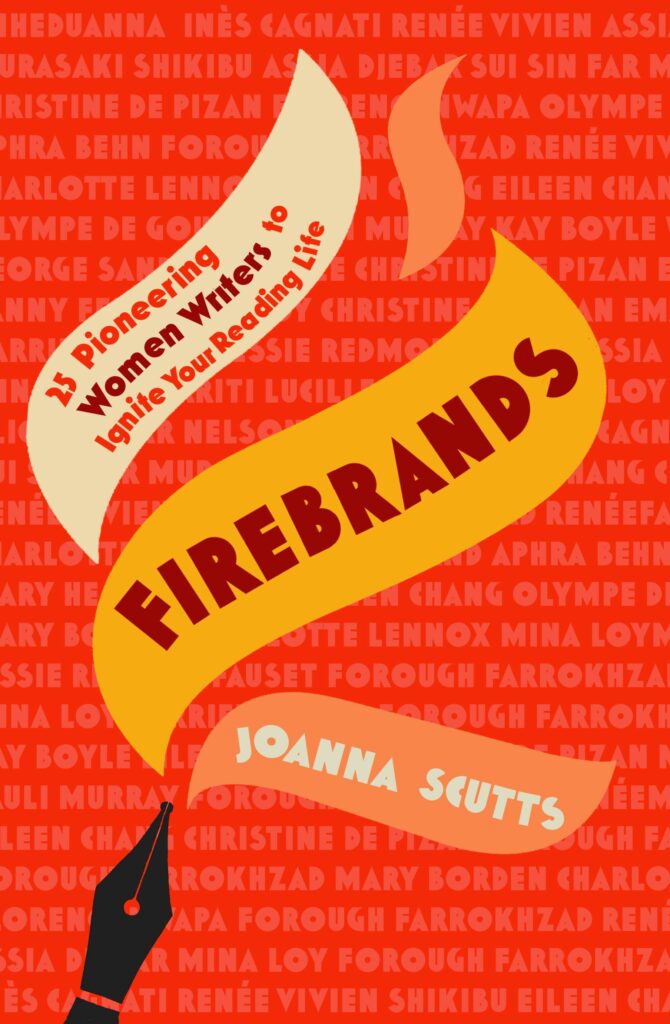

The Trailblazing Women Who Dared to Be Different

Firebrands author Joanna Scutts explains why she set out to re-examine the literary canon and highlight the fantastic authors that have been underappreciated and overlooked throughout history.

Even a keen and curious reader might be forgiven for assuming that literature, going back a generation or two, never had a place for women. The handful of familiar names – Jane Austen, the Brontës, Woolf – can seem like exceptions proving that rule.

Yet women have always been storytellers, poets and playwrights, the guardians of history and myth, family lore and social ritual. Where they have been excluded, historically, is from education and from power. If they managed to become writers against the odds, they found their reputations and legacies were vulnerable.

Even if they were popular and widely read (and often because they were popular and widely read) their presence, on bookshelves and syllabi, and in the wider cultural consciousness, was often fleeting. Scores of once-famous writers have been lost – overlooked, underestimated, dismissed, neglected and forgotten – in this way, and too many brilliant, funny, weird and incendiary voices remain muted.

Too many brilliant, funny, weird and incendiary voices remain muted

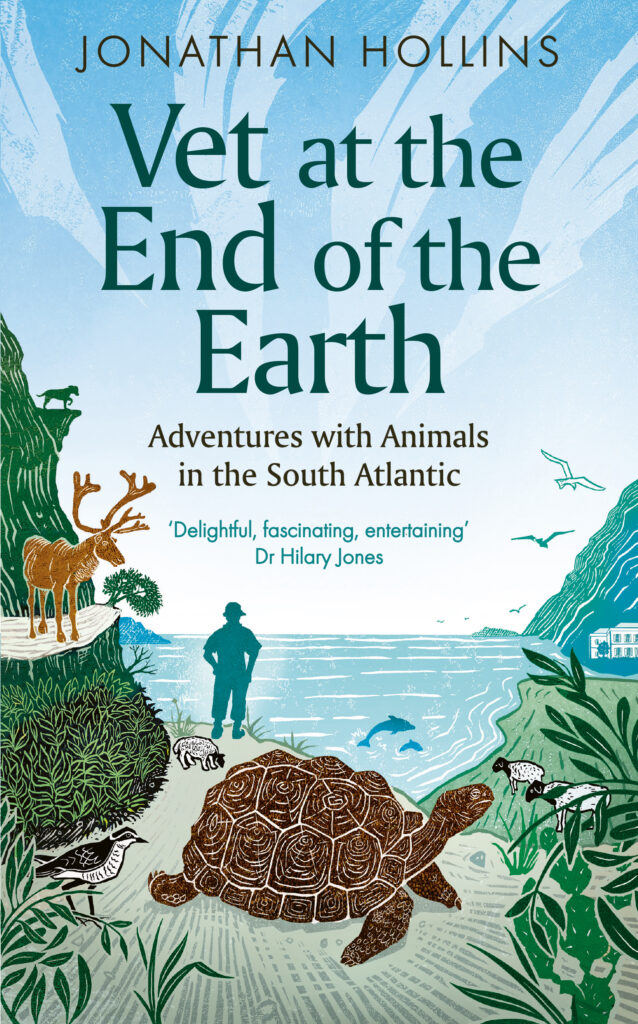

This book sets out to change that, by introducing readers to twenty-five daring women whose work still has the capacity to shake up our expectations and spark new conversations. They produced everything from temple hymns to muckraking journalism, via poetry, memoir, drama, fiction, film and innumerable hybrid literary forms.

In terms of class and occupation, they include aristocrats and bohemians, workers and warriors, immigrants and servants, farmers’ daughters and heiresses. They were married and widowed, mothers and spinsters, straight and queer. Some of these women were in their twenties when they did their best work, but just as many were in their forties or seventies. The variety shows us there is no single way to be a woman writer.

There is no single way to be a woman writer

And even that label should give us pause. I use it because, for the most part, these writers lived and worked in times and places where sex was destiny, and the gender binary was rigidly enforced and violently policed.

For the nonbinary Pauli Murray and the gender-rebellious George Sand, in particular, the label ‘woman writer’ feels neither accurate nor sufficient. It says more about the reception of their work than the way they lived in the world.

When our women’s literary canon contains just a handful of names, it’s easy to think that only a certain kinds of women can write. Money makes it possible and children, surely, make it impossible.

But here we have Kay Boyle and Lucille Clifton, both mothers of six, and both prolific, prize-winning, politically active writers: perennially short of cash, yet humane and courageous in their art throughout their lives.

Here too we have writers like Mary Borden and Mary Heaton Vorse, witnesses to war and political violence, challenging the notion of what women “should” write about. History acts on them all, but for some more dramatically than others.

The biographical details of Olympe de Gouges, caught up in the throes of the French Revolution, or of Juana Manuela Gorriti, fleeing across borders amid the turbulence of nineteenth-century Latin American politics, themselves read like stories. My title is borrowed from Woolf, a term she used in A Room of One’s Own for women of the nineteenth century who dared to be writers.

A firebrand is a burning piece of wood

A firebrand originally named a burning piece of wood, used to light a path or ignite a blaze – a term dating back to the era of one of my earliest subjects, the fourteenth-century poet and feminist foremother Christine de Pizan.

Later, it came to describe, figuratively, a person who lit a trail, like Christine herself (straight to hell, her critics said.) Taken together, these profiles demonstrate the breadth and scope of women’s writing and of women’s identities throughout literary history. Nobody here is a writer you should read, a missing link in a secure chain of “great” literature. I don’t think that’s how it works.

Rather, they’re collected here for what they can spark in us, their newest readers. For how they might open us up to new subjects, experiences and styles, and help us look at the past in new ways—if nothing else, putting paid to our assumptions about silent, cloistered women. In that spirit, this book is an invitation to the pleasure of discovery, to what I hope is a rich, rewarding literary feast

In twenty-five witty and vibrant biographical essays, Firebrands introduces us to the brilliant and complex women writers that every discerning reader should know about

Essay Collection

Hardback

26 September 2024

ISBN 9780715655269

‘Scutts’ companionable and sprightly volume of literary women deftly questions the gatekeeping terms of the literary canon, delivering profound insights with a lightness of touch’ Catherine McCormack, author of Woman in the Picture

From Murasaki Shikibu, the Japanese author of one of the world’s earliest novels, and Christine de Pizan, a poet in the royal court of medieval France, to Harriet Jacobs, who drew the world’s attention to the horrors of slavery through her own experience, Firebrands explores the lives and works of twenty-five extraordinary women writers.

Joanna Scutts guides the reader through the centuries and across the world, hailing the fascinating lives and astonishing literary achievements of these women who dared to write against the odds. Brilliantly researched and fiercely uncompromising, Firebrands is a reminder to all of us to question what – and who – is considered part of the canon.