What's in a Name?

Ian Moore explains how constructing the title of your book is as important as the work itself, and where he came up with the witty title for the latest instalment in the Juge Lombard series.

Anybody who’s had to go through the personal torture of choosing a baby’s name knows the problem. What does the name mean? Who else has the name? Didn’t you once read something somewhere that…

It’s a situation fraught with anxiety and doubt. This is your baby; this name is for life. Well, not to put too fine a point on it, but we fragile, precious authors feel much the same about the titles of our books.

This has been a labour of love, you’ve nurtured it and will, in most instances, cherish it for life. It needs a name though, a title, that will live on. It must delight, intrigue and question. And it’s really difficult to get right.

In many ways authors, as with some parents, are too close to the subject to give a balanced opinion. Personally, I cannot sit down to write a new book without the title already sorted in my head

It may change along the way

It may change again when the thing’s finished. That’s the time when wiser, more focused heads get involved, proffering advice and experience like grandparents at a Christening who whisper, ‘There was a Dominic already in the family, remember? Bad lot that one.’

I’m very proud of the title of Dead Behind the Eyes. It has personal history, it’s relevant to the story on a number of levels, and it’s original.

I have been a stand-up comedian for over twenty-five years, and it’s a hard job. Now look, when I say it’s a hard job, I know it’s not exactly early morning dustbin collection, (which I’ve done), minder to a dodgy businessman, (which I’ve done), or sulphur mining in Indonesia, (which I haven’t done).

So, it’s a hard-ish job, then

Not the stage bit, that, nine times out of ten, is easy. That’s the fun part. No, it’s the budget. Cheap time of the day travel; eating a Ginsters pasty at two in the morning because there’s nothing else; starting work at eleven pm; overnight Megabus coaches; no social life; blokes at the bar saying, ‘’ere’s one you can use!’ and so on.

And every now and then the road gets too hard. You find yourself on stage listless, a parody of your own act, too tired to change gear and generally missing the belief or the energy to do the job.

Audiences don’t always see it, but other comics do and if they’re good friends, they’ll tell you. Actually, if they’re rivals, they’ll tell you too. They’ll take you surreptitiously aside, put a hand on your shoulder and say quietly, ‘Are you OK? You looked Dead Behind The Eyes up there.’

A good friend did that for me

It saved my career. On one level my main character, Matthieu Lombard, is asking himself that question. Sidelined by the magistrature, barely tolerated by distrusting colleagues and grieving over the loss of his wife, he’s reached a point many of us reach in life.

Is this all there is? Will a change of scenery make a difference?

And then a headless corpse washes up on the banks of the river Loire.

Surely this is the spark he needs. His interest should be piqued, the natural curiosity of the investigator and the desire for truth and justice, should now kick in like a jolt of electricity reawakening the Zombie mind…

Well obviously, you’ll have to read the book to find that out, and more besides. I will give this away though; Lombard recognises something of himself in the victim and it hurts. Now how can a headless corpse be Dead Behind The Eyes?M

A HEADLESS MAN. A MISSING GIRL. A LIFE RULED BY SECRETS...

Crime Fiction

Hardback

07 November 2024

ISBN 9780715655498

‘An engrossing, slickly plotted policier that will leave you wanting more’ Tom Benjamin, author of the Daniel Leicester mysteries

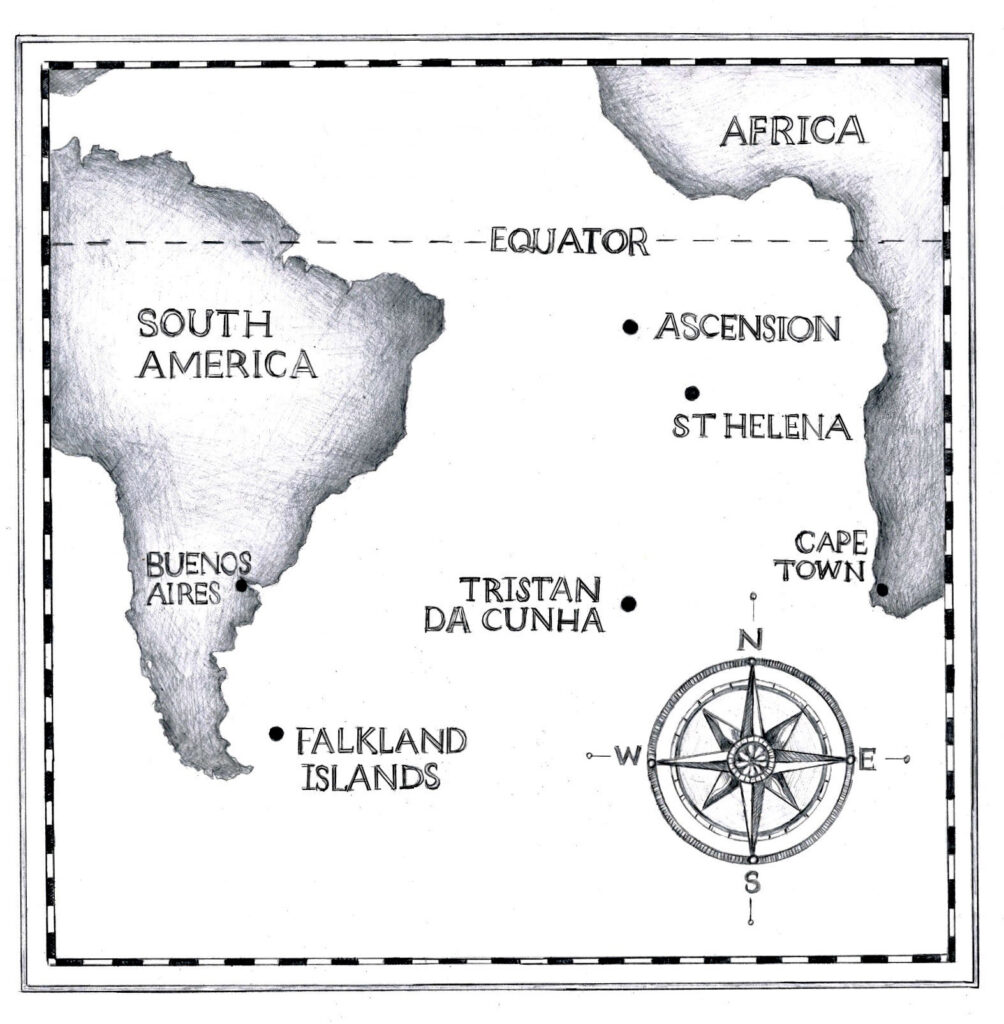

When a decapitated body washes up on the banks of the River Loire in the ancient city of Tours, the reluctant juge d’instruction Mattiew Lombard is brought in to lead the investigation.

But when Lombard’s young niece appears, the inquiry changes course. Suddenly immersed in another world – one of eco-terrorism, bio-medical research, French aristocracy and the violent forgotten underbelly of society – Lombard begins to make unexpected connections.

Can the brutal murder of a lonely man really be justified by a noble cause? Or are good intentions hiding darker motives, more cynical and more deadly?