1. FC Union Berlin: 10 Things You Should Know

1. FC Union Berlin are a football club that play in the German Bundesliga – the top division of German football.

The team from south-east Berlin will compete in the UEFA Champions League for the first time in their history in the 2023/24 season.

We’ve listed 10 things you should know about Die Eisernen (The Iron Ones)…

Jump to:

- The Origins of Union Berlin

- Union Berlin and rivalries

- How to pronounce ‘Union’

- Union Berlin fans built their own stadium

- Union Berlin’s love of the forest

- Union Berlin fans bled for their club

- Union Berlin’s unique corner flags

- The historic curse of Union in Europe

- The World Cup Living Room

- The Union Berlin Christmas Carol Service

1. The Origins of Union Berlin

The exact date of Union Berlin’s formation is hard to say. In its current form, the club has only been around since 1966. But its roots go far deeper, stretching from the German Empire to the building of the Berlin Wall, via a revolution and two world wars.

Its earliest ancestor was SC Olympia Oberschöneweide (1906), before they moved to their current home in Köpenick as SC Union Oberschöneweide in 1920.

Did Union-know?

When SC Union played Hamburger SV in the final of the German Championship in June 1923 the cost of a kilo of rye bread was in the hundreds of billions of marks.

After Germany was divided in the Cold War, the club split in two, with SC Union 06 in the West and the old club remaining at the Alte Försterei.

In 1951, the latter merged with a neighbouring club to form BSG Motor, dropping ‘Union’ from their name altogether and adopting the red-and-white which they still wear today.

When 1966 saw a drastic reform of East German football, the East Berlin club finally became the club we know today: 1. FC Union Berlin.

After Germany was divided in the Cold War, the club split in two, with SC Union 06 in the West and the old club remaining at the Alte Försterei. In 1951, the latter merged with a neighbouring club to form BSG Motor, dropping ‘Union’ from their name altogether and adopting the red-and-white which they still wear today.

When 1966 saw a drastic reform of East German football, the East Berlin club finally became the club we know today: 1. FC Union Berlin.

Köpenick, in the south-east of Berlin, is the home of Union Berlin. Only slightly to the north-west of Köpenick on the map, you can see Union’s ancestral home of Oberschöneweide.

2. Union Berlin and rivalries

The rivalry between Union Berlin and Hertha Berlin is notorious, especially following Union’s promotion to the Bundesliga in 2019. As of August 2023, Union have won the last five fixtures between the two clubs. Following relegation in the 2022/23 season, Hertha now play in the 2. Bundesliga.

However, Union’s traditional and fiercest rivals are Berliner FC (BFC) Dynamo. Though the two sides have not played a league game against each other since 2006, the once fierce rivalry is still a defining feature of Union’s identity.

In the Communist era, BFC were affiliated with Erich Mielke’s Stasi secret police. And the club’s advantages on the pitch were undeniable: they won ten titles in a row from 1979 to 1988 while Union suffered multiple relegations.

This inequality helped shape Union’s character as footballing outlaws in a world where the wrong people always won.

Things, however, have changed since the millennium. While Union began their march towards the Bundesliga, BFC have languished between the fourth and fifth tiers of German football.

3. How to pronounce 'Union'

It is just ‘Union’, not ‘the Union’ or ‘a Union’.

To write or read Union like the English word ‘union’ is wrong, because that is not how Unioners themselves pronounce it.

The name is pronounced oon-yawn, rather than yoo-nyun. Grammatically, therefore, when you refer to a supporter it is ‘an Union fan’ rather than ‘a Union fan’.

4. Union Berlin fans built their own stadium

Union Berlin play their home games at Stadion an der Alten Försterei in Köpenick, which is in the south-east of Berlin.

Union have played there for 102 years, after relocating from Oberschöneweide in 1920. The stadium is the oldest, most enduring element of the club’s identity: it’s older than the colours, the badge and the oldest supporters.

By the 1990s, the Alte Försterei was effectively unfit for purpose and plans were drawn for a rebuild. However, Union had very little money and only a handful of employees who were able to set up and run a fully functioning construction site.

So, during the 2008/09 season, 2,333 men and women – most of them volunteers – worked more than 140,000 hours to transform the Alte Försterei from a crumbling wreck into one of modern football’s most distinctive stadiums.

Did Union-know?

The fans’ efforts are now immortalised in a beer garden on the southern side of the stadium. In the shadow of the terraces stands a tall, stout column made of iron girders, which is decorated with metal plaques bearing the name of every single person

who signed up to help.

5. Union Berlin's love of the forest

Trees are part of the club’s soul.

The Alte Försterei is on the urban edges of the forests and lakes which surround Berlin. To the north-west of the stadium is the Wuhlheide, a sprawling woodland park which stretches across the south-east of the city.

The club’s main offices are in the Old Forester’s House which gives the stadium its name.

Did Union-know?

When spectators were banished from stadiums during the pandemic, many Union fans simply climbed the trees to watch and cheer on their team from outside.

Union fans sing this song in tribute to their sylvan home:

“In uns’rem Stadion

In der Hauptstadt

In der wunderschönen, immergrünen Alten Försterei”

Translated to English, it reads:

“In our stadium

In the capital

In the beautiful, evergreen Alte Försterei”

Do you want to discover more Union Berlin songs? Check out Union in Englisch’s page of Union songs.

6. Union Berlin fans bled for their club

Would you bleed for you club? Because Union fans did. Literally.

In 2004, Union were so short of cash that they were on the brink of losing their league licence and being banished back into the wilderness of non-league football.

There followed a mammoth fundraising effort. At the centre of it was the Bleed for Union initiative, which allowed fans to donate blood in Union’s name. The ten euros compensation fee which was ordinarily paid to the blood donor themselves was wired directly to the football club.

7. Union Berlin's unique corner flags

Where most clubs just have their emblem or plain block colours on their corner flags, Union have a face. Designed by artist and Union supporter Andora, Der kleine Biss (‘The Little Bite’) flies from all four corners of the Alte Försterei. Literally.

According to Andora, it represents the bite Unioners have always had, ever since the beginning.

You can read more about Andora here in this Der Tagesspiegel article written by Scheisse! We’re Going Up! author Kit Holden.

8. The historic curse of Union in Europe

Did Union-know?

Union have qualified for Europe five times in their history. Three of them have come in the last three seasons.

Oddly, Union’s adventures in Europe have always been somewhat cursed.

When Union qualified for the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1968, their dreams of travelling the continent were immediately dashed by an escalation of the Cold War. In the fallout from the Soviets’ brutal suppression of the Prague Spring, several Eastern Bloc countries, including East Germany, decided to boycott UEFA competition in the 1968/69 season.

Thirty-three years later, it was an international terrorist incident. In 2001, Union’s UEFA Cup first-round tie against Finnish side Haka Valkeakoski was originally scheduled for 13 September but was postponed after the 9/11 attacks in New York.

Two decades on, Union qualified for the 21/22 UEFA Conference League competition, challenging on the European stage for the first time in 20 years.

Cue the next international catastrophe. In the midst of the Covid pandemic, public health restrictions meant Union had to play their European home games in front of half-full stadiums. And to make matters worse, they couldn’t even play on the hallowed turf of the Alte Försterei. The stadium didn’t comply with UEFA regulations, meaning Union had to instead play at Hertha’s Olympiastadion.

Though Union had to continue playing their 2022/23 UEFA Europa League home ties at the national stadium, the campaign was crisis-free.

We wonder what their 2023/2024 UEFA Champions League adventure – Union Berlin’s first ever – has in store…

9. The World Cup Living Room

In 2014, the Alte Försterei was transformed into a ‘World Cup Living Room’, where fans could watch Germany games on the big screen. The stands were decorated with retro East German-style wallpaper, and the pitch was adorned with around 800 sofas which the spectators had brought from their own homes.

Das ist cosy!

10. The Union Berlin Christmas Carol Service

On the evening of 23 December 2003, a large group of Union fans snuck into the stands at the Alte Försterei and sang Christmas carols to banish away the blues felt by poor results in the league. The Union Christmas Carol Service – known as Weihnachtssingen – was born. Little did they know at the time that it would become a roaring success in years to come.

By the late 2010s, the so-called Weihnachtssingen had become a world-famous tradition, attracting hundreds of reporters and tourists from around the globe to the Alte Försterei every 23 December. With nearly 30,000 attendees every year, it is now one of the biggest Christmas events in the city.

Jump to:

- The Origins of Union Berlin

- Union Berlin and rivalries

- How to pronounce ‘Union’

- Union Berlin fans built their own stadium

- Union Berlin’s love of the forest

- Union Berlin fans bled for their club

- Union Berlin’s unique corner flags

- The historic curse of Union in Europe

- The World Cup Living Room

- The Union Berlin Christmas Carol Service

Want to find out more about Union Berlin?

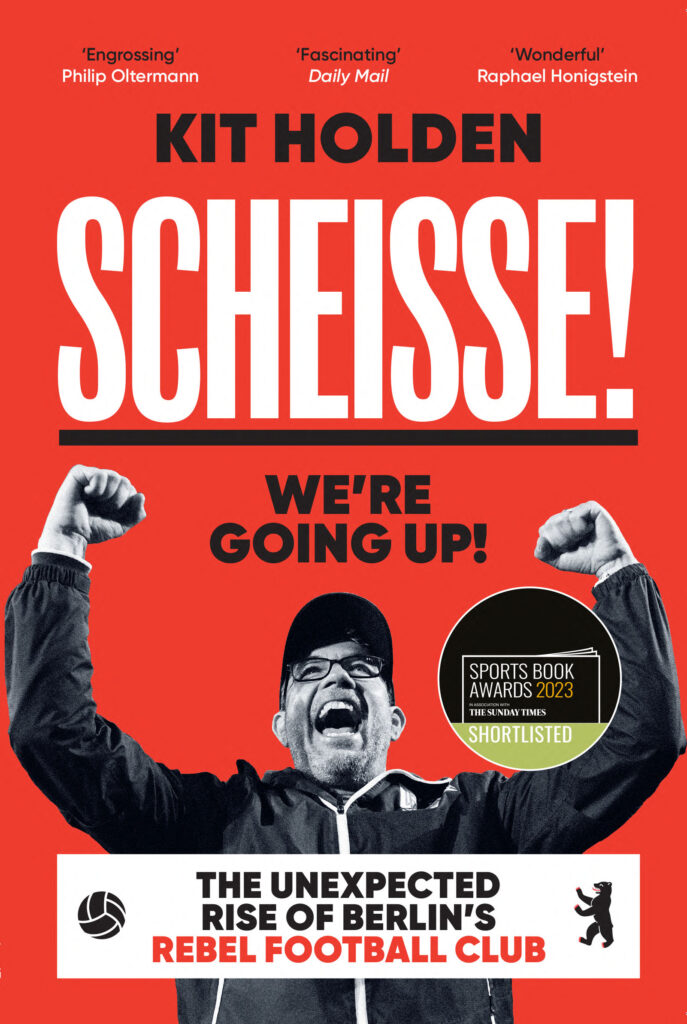

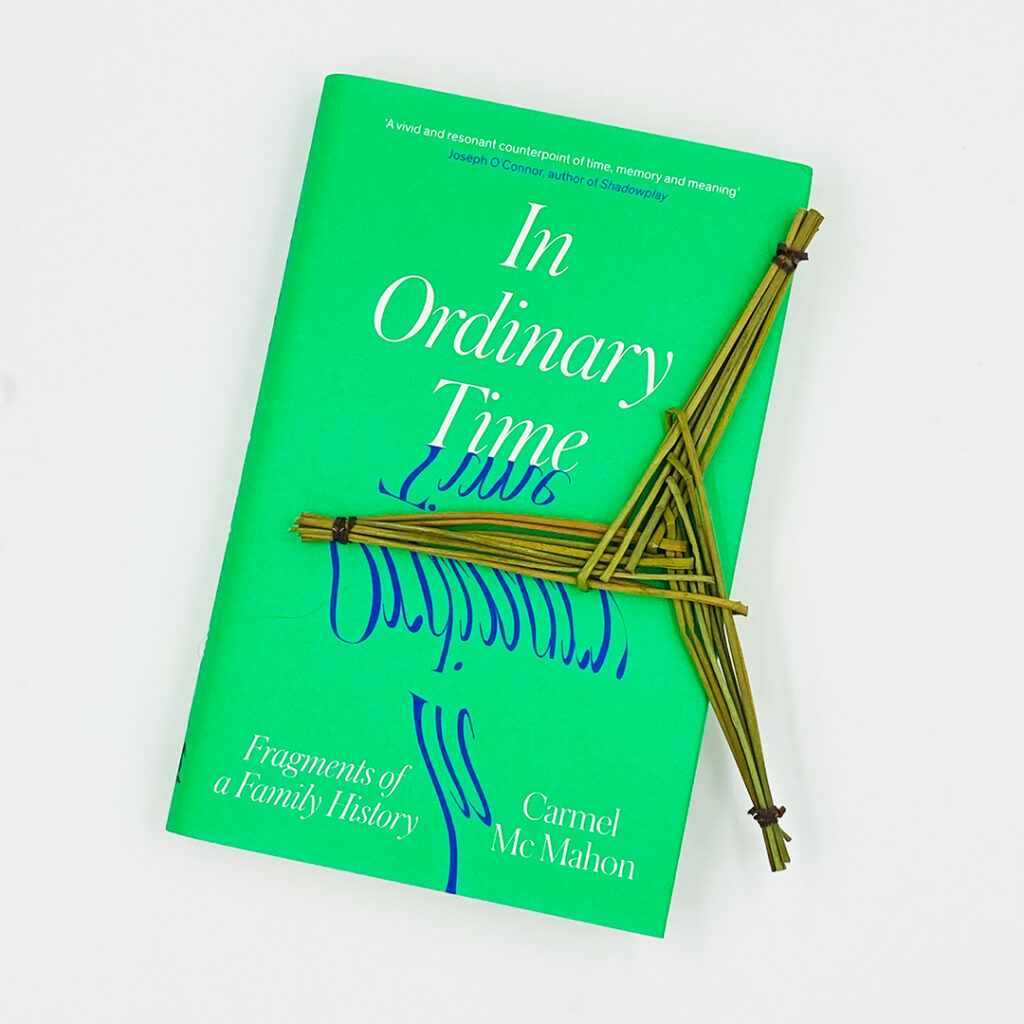

SHORTLISTED FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES SPORTS BOOK AWARDS 2023 (FOOTBALL BOOK OF THE YEAR)

No football club in the world has fans like 1. FC Union Berlin. The underdogs from East Berlin have stuck it to the Stasi, built their own stadium and even given blood to save their club. But now they face a new and terrifying prospect: success.

Scheisse! tells the human stories behind the unexpected rise of this unique football club. But it’s about more than just football. It’s about the city Union call home. As the club fight to maintain their rebel spirit among the modern football elite, their trajectory mirrors that of contemporary Berlin itself: from divided Cold War battleground to European capital of cool.

Praise for Scheisse! We're Going Up!

Did Union-know?

The cover for Scheisse! We’re Going Up! was inspired by a tifo of coach Urs Fischer raised by Union ultras in the famous Waldseite (forest stand) behind the goal at the north end of the stadium. It appeared in Union’s second ever Bundesliga home game in 2019. A few hours later, they were celebrating a sensational 3-1 win over Borussia Dortmund. © 1. FC Union Berlin

Reader reviews

‘This was as much a social and political history of Berlin as a football book. Like many other fans I have been taken by surprise and fascinated by the recent rise of Union Berlin and this well written and researched book by Kit Holden digs well beneath the surface and puts their achievements fully into context. Peppered with fan anecdotes this is a rollicking and enjoyable read. Highly recommended’

Greville Waterman, NetGalley

‘What a brilliant book! This is a detailed, thoughtful and intelligent chronicle of the rise and fall… and rise and fall… and rise and rise of a football club which has a real identity as an integral part of the tough East Berlin community in which it is situated. The format of the book, telling the story of Union Berlin’s history and evolution through the perspectives of those people most closely involved brings realism and a real sense of what the club means to those people… I highly recommend this book to football fans and any non-football fans interested in a true “David and Goliath” tale told against the backdrop of a fascinating period of post-war European history’

Tony McMullin, NetGalley

‘Holden tells the history of the club and the city through interviews with a variety of fans and officials. It’s an inspired choice and the narrative weaves excellently between personal recollections and the over-arching story of both the city and the club’s past, present and future. The book is packed with stories and recollections of fans and their passion oozes out of every page. It wonderfully captures the essence of the club and what makes it special… Scheisse! is an absolutely brilliant book. It captures the very essence of why sport matters’

Brendan Crowley, All Sports Book Reviews

‘An outstandingly fun read, this will make any reader a fan of Union… I can definitely see me egging them on in the majority of their games next season, and more relevantly, egging this book about them on to the heights it deserves to achieve’

John Lloyd, NetGalley

‘Union Berlin are one of the most fascinating football clubs in Europe. Their story and their remarkable success on the pitch of the last few years is told really well by Kit Holden. In each chapter a supporter is interviewed about a particular milestone that has shaped this unique club. It is also a history of the changing city of Berlin from the cold war to today. I loved it’

Jim Hanks, NetGalley

Don’t only set your sites on the Big Four publishing houses and their imprints. See if your local area has a publishing house; you will be surprised with whom you find.

Don’t only set your sites on the Big Four publishing houses and their imprints. See if your local area has a publishing house; you will be surprised with whom you find.