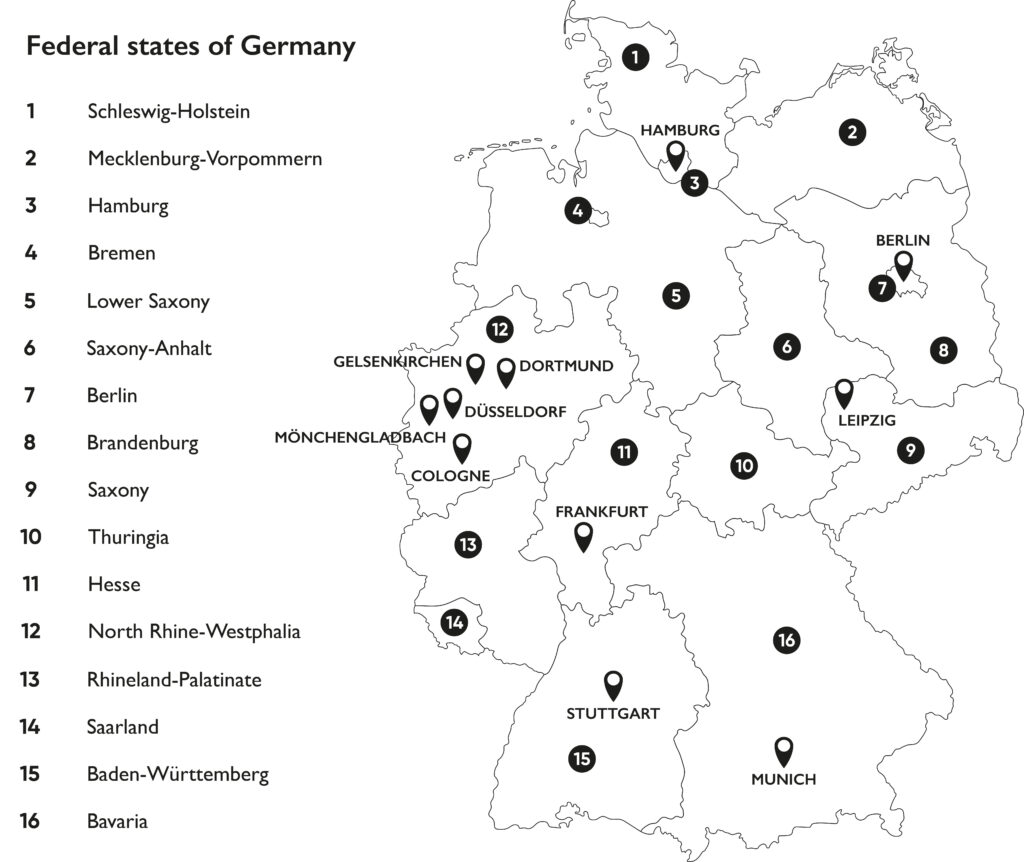

What can football really tell us about Germany, the Euro 2024 hosts?

This summer, the eyes of football fans worldwide will turn to Germany as it hosts Euro 2024.

For many, the country seems familiar territory: a footballing behemoth with clubs as famous as its beer and its cars. But, if you look closer, the beautiful game can offer a deeper understanding of Europe’s powerhouse.

So, what can football really tell us about Europe’s powerhouse? Let’s find out.

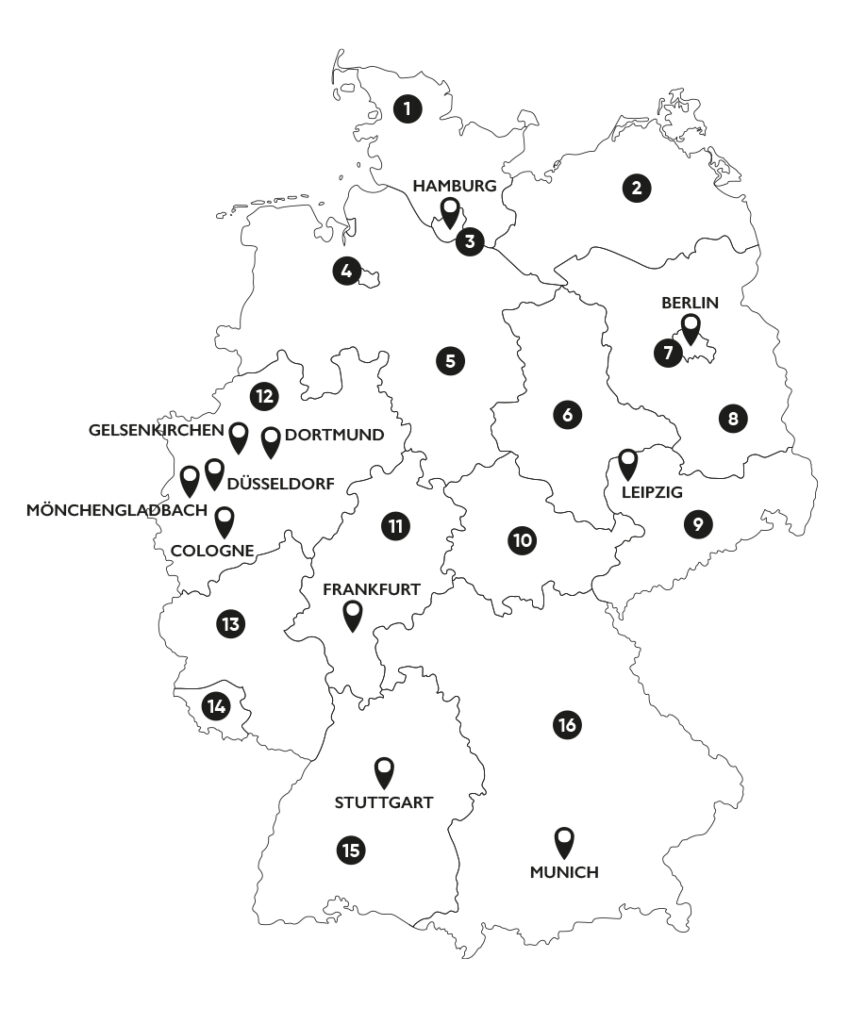

Modern Germany

Leipzig

Saxony

Cities: Leipzig

Football teams:

RB Leipzig (red, white)

1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig

(yellow, blue)

BSG Chemie Leipzig (green, white)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

Red Bull Arena (RB Leipzig)

Euro 2024 fixtures in Leipzig:

18/06: Portugal vs Czechia (20:00 BST)

21/06: Netherlands vs France (20:00 BST)

24/06: Croatia vs Italy (20:00 BST)

02/07: Round of 16 – 1D vs 2F (20:00 BST)

About:

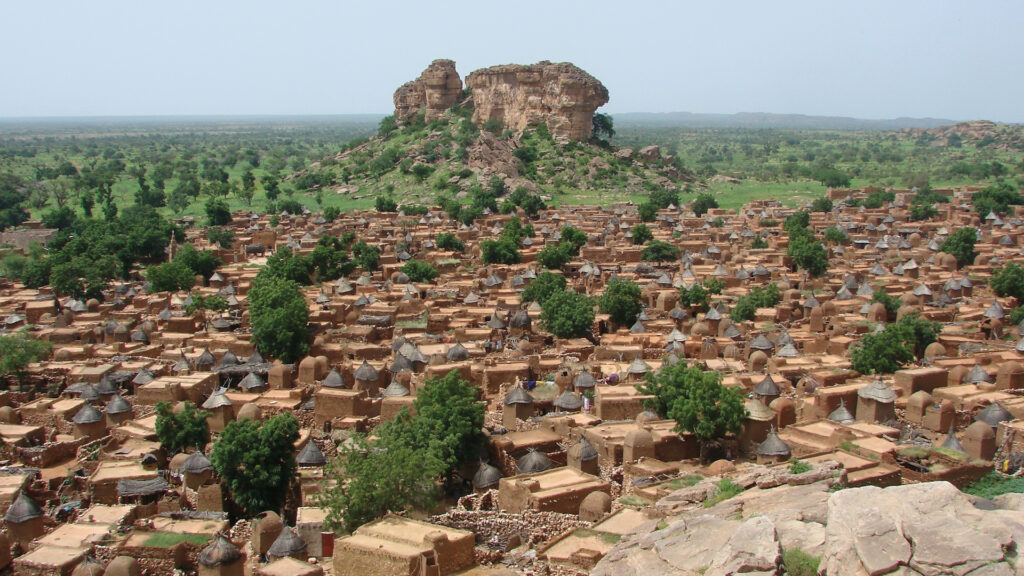

Leipzig is the birthplace of the German FA and one of the most important towns in the country’s history.

Yet today, the eastern city is the most hated place in German football. While nouveau-riche RB Leipzig are seen by many fans as a threat to the game’s culture and traditions, grand old East German clubs like Lokomotive and Chemie are struggling to stay alive in the lower leagues.

In the city of Bach, Wagner and Goethe, the beautiful game is a matter of life and death. And three decades after German reunification, Leipzig’s football culture war exposes the deep divides which still run between the former East and the former West.

The Rhineland

North Rhine-Westpahlia

Cities: Köln (Cologne), Düsseldorf, Mönchengladbach

Football teams:

1. FC Köln

(white, red)

Fortuna Düsseldorf (red, white)

Borussia Mönchengladbach (black, white, green)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

RheinEnergieStadion (1. FC Köln)

Düsseldorf Arena (Fortuna Düsseldorf)

Euro 2024 fixtures in Cologne:

15/06: Hungary vs Switzerland (14:00 BST)

19/06: Scotland vs Switzerland (20:00 BST)

22/06: Belgium vs Romania (20:00 BST)

25/06: England vs Slovenia (20:00 BST)

30/06: Round of 16 – 1B vs 3A/D/E/F (20:00 BST)

Fixtures in Düsseldorf:

17/06: Austria vs France (20:00 BST)

21/06: Slovakia vs Ukraine (14:00 BST)

24/06: Albania vs Spain (20:00 BST)

01/07: Round of 16 – 2D vs 2E (17:00 BST)

06/07: Quarter-final (17:00 BST)

About:

On the banks of the Rhine, people don’t take life too seriously. Cities like Cologne and Düsseldorf lie in the heart of carnival country, and their football clubs are known for wacky seasonal shirts, beloved billy-goat mascots and calamitous on-field fortunes.

But the Rhineland is also a place of power. Home to the biggest Catholic Church in Europe, it is also where the West German state and modern democratic Germany were forged after the Second World War.

Clubs like 1. FC Köln, Fortuna Düsseldorf and Borussia Mönchengladbach may have lost some of their old grandeur, but their enduring cultural clout still speaks of a country whose foundations lie in the west, far from the current capital Berlin.

The Ruhr

North Rhine-Westpahlia

Cities: Dortmund, Gelsenkirchen

Football teams:

Borussia Dortmund (BVB)

(yellow, black)

FC Schalke 04 (blue, white)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

Westfalenstadion, Dortmund (BVB)

Veltins Arena, Gelsenkirchen (Schalke 04)

Euro 2024 fixtures in Dortmund:

15/06: Italy vs Albania (20:00 BST)

18/06: Türkiye vs Georgia (17:00 BST)

22/06: Türkiye vs Portugal (17:00 BST)

25/06: France vs Poland (17:00 BST)

29/06: Round of 16 – 1A vs 2C (20:00 BST)

10/07: Semi-final (20:00 BST)

Fixtures in Gelsenkirchen:

16/06: Serbia vs England (20:00 BST)

20/06: Spain vs Italy (20:00 BST)

26/06: Georgia vs Portugal (20:00 BST)

30/06: Round of 16 – 1C vs 3D/E/F (17:00 BST)

About:

For more than a century, the coal mines and steel works of the Ruhr were the engine of Germany’s formidable economic power.

They also gave rise to some of the country’s biggest and most successful clubs, and in the post-industrial age, it is footballing giants like Borussia Dortmund and Schalke 04 which have helped the Ruhr retain its sense of community and identity.

Yet as the golden age of coal recedes further into history, the clubs and their cities both face the same dilemma. How do you stay successful while also staying true to your working-class roots?

Stuttgart (Swabia)

Baden-Württemberg

Cities: Stuttgart

Football teams:

VfB Stuttgart

(white, red)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

MHPArena

Euro 2024 fixtures in Stuttgart:

16/06: Slovenia vs Denmark (17:00 BST)

19/06: Germany vs Hungary (17:00 BST)

23/06: Scotland vs Hungary (20:00 BST)

26/06: Ukraine vs Belgium (17:00 BST)

05/07: Quarter-final (17:00 BST)

About:

Ever since Gottlieb Daimler invented the four-wheeled automobile in Stuttgart back in 1886, Germany has been a country of cars, and “Made in Germany” has been the ultimate seal of quality for motorists across the world.

Stuttgart-based companies like Porsche and Mercedes-Benz may export luxury goods around the globe, but their headquarters and their spiritual home is still in Germany, among the straight-laced, spendthrift “Swabians” of the south-west.

Little wonder, then, that the fortunes of five-time champions VfB Stuttgart are still intimately entwined with the car companies next door.

Frankfurt

Hesse

Cities: Frankfurt

Football teams:

Eintracht Frankfurt

(red, black, white)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

Deutsche Bank Park

Euro 2024 fixtures in Frankfurt:

17/06: Belgium vs Slovakia (17:00 BST)

20/06: Denmark vs England (17:00 BST)

23/06: Switzerland vs Germany (20:00 BST)

26/06: Slovakia vs Romania (17:00 BST)

01/07: Round of 16 – 1F vs 3A/B/C (20:00 BST)

About:

When Germany last hosted a major football tournament in 2006, it was hailed as the “summer fairytale”, as the team reached the semi-finals of the World Cup and the public launched into an unprecedented display of national confidence.

Yet even today, the legacy of that tournament is disputed and many Germans still feel queasy about waving the flag. In the country which committed the Holocaust, national pride and identity are always complicated. What does it mean to be German in the 21st century? How does a country deal with the horrors of its past? And is the spectre of political extremism once again on the rise?

In Frankfurt, where German democracy was born and the perpetrators of Auschwitz were later put on trial, those questions come into sharp focus. Especially when there’s a football tournament on.

Hamburg

Hamburg

Cities: Hamburg

Football teams:

Hamburger SV (HSV)

(blue, white, black)

FC St. Pauli (brown, white)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

Volksparkstadion (HSV)

Euro 2024 fixtures in Hamburg:

16/06: Poland vs Netherlands (14:00 BST)

19/06: Croatia vs Albania (14:00 BST)

22/06: Georgia vs Czechia (14:00 BST)

26/06: Czechia vs Türkiye (20:00 BST)

05/07: Quarter-final (20:00 BST)

About:

If there is one place where the fight against the far-right takes place on the football terraces, it is Hamburg.

The port city’s on-field rivalry is a clash of two ideological traditions. HSV are one of the grand old statesmen of the German game, and their fanbase is a broad church which unites people from all walks of life. FC St. Pauli, by contrast, are the counter-culture revolutionaries from the red-light district and Europe’s most famous anti-far-right football club.

Establishment or underdog? Compromise and consensus or radicalism and revolution? This is a derby which makes a mockery of the old adage that football and politics don’t mix. In Hamburg, football is always political. But in football, as in real life, there is more than one way to do politics.

Munich

Bavaria

Cities: Munich

Football teams:

FC Bayern Munich

(red, white, blue)

TSV 1860 Munich (blue, black)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

Allianz Arena (FC Bayern)

Euro 2024 fixtures in Munich:

14/06: Germany vs Scotland (20:00 BST)

17/06: Romania vs Ukraine (14:00 BST)

20/06: Slovenia vs Serbia (14:00 BST)

25/06: Denmark vs Serbia (20:00 BST)

02/07: Round of 16 – 1E vs 3A/B/C/D (17:00 BST)

09/07: Semi-final (20:00 BST)

About:

“In Bavaria, there is a symbiosis between laptops and lederhosen,” said then German president Roman Herzog back in 1998.

A deeply conservative Catholic region on the one hand, Bavaria is also home to some of Germany’s most successful exports, from Adidas and BMW to Beckenbauer and Bayern Munich.

Here, they say, tradition and modernity go hand in hand. This is where the salt of the earth become global market leaders and where world-class athletes are still made to dress up in traditional garb and sink litres of beer at Oktoberfest.

Laptops and lederhosen is the winning formula which has made Bayern a modern superclub and helped make Germany one of the leading economies in the world. But does it still work?

Berlin

Berlin

Cities: Berlin

Football teams:

1. FC Union Berlin

(red, white, yellow)

Hertha BSC (blue, white)

Euro 2024 stadiums:

Olympiastadion (Hertha BSC)

Euro 2024 fixtures in Berlin:

15/06: Spain vs Croatia (17:00 BST)

21/06: Poland vs Austria (17:00 BST)

25/06: Netherlands vs Austria (17:00 BST)

29/06: Round of 16 – 2A vs 2B (17:00 BST)

06/07: Quarter-final (20:00 BST)

14/07: Final (20:00 BST)

About:

Berlin football has always been shaped by its history. Destroyed by war and divided for half a century afterwards, the city was always a ramshackle capital, a place of revolution, sub-culture rather than power and grandeur.

It’s two major clubs, Hertha BSC and 1. FC Union, emerged on either side of the Wall, and their respective histories of on-field failure tell mirror-image stories of a divided city.

But now, both Berlin and its football are changing once again. While some fear gentrification and rising prices are eating away at the city’s soul, there is also cause for hope. In football, new powers are rising and new revolutions are taking shape.

Here, perhaps more than anywhere else, the game reflects a country in flux.

Want to find out more?

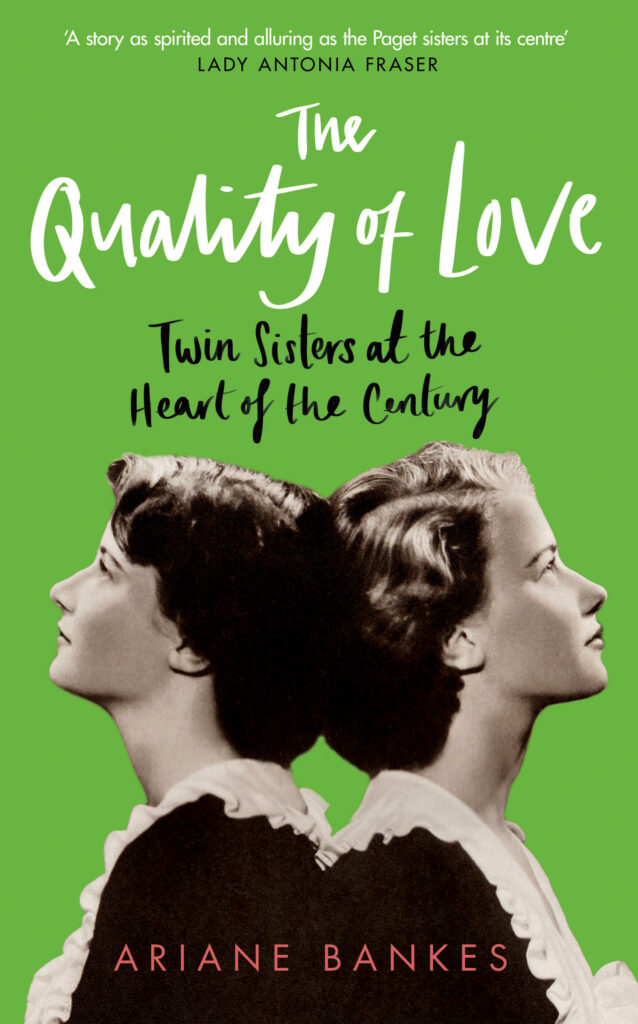

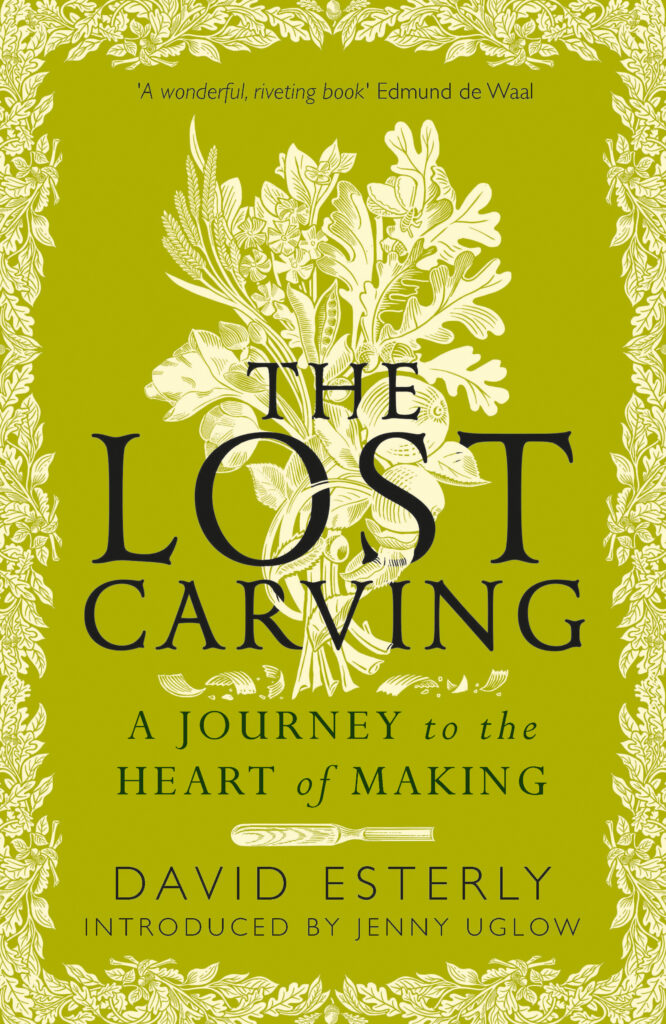

Beyond the booze and the bratwurst: what football really tells us about Germany, the UEFA Euro 2024 hosts

Played in Germany takes us on a journey through modern Germany’s football heartlands in search of the issues that define it. Through the stadiums, songs and simmering resentments of football, Kit Holden sheds light on a nation so diverse and divided that the only thing that really unites it is the game itself.

‘Immaculately researched, entertainingly written’ Jonathan Liew

‘Vivid detail’ John Kampfner

‘An intimate portrait of Germany’ Archie Rhind-Tutt