Guest post

Forward, backward, and forward again for women’s rights

Joanna Scutts reflects on the long and complicated fight for women’s suffrage in the twentieth century and how we can find hope for the future in their story.

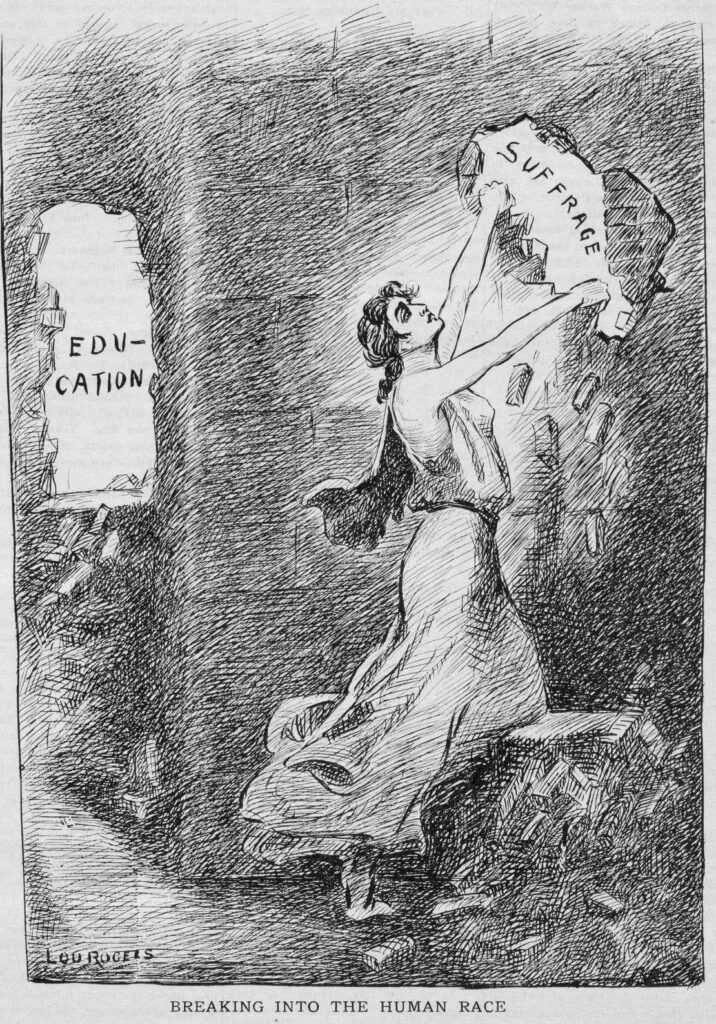

The fight for suffrage was a long, complicated story

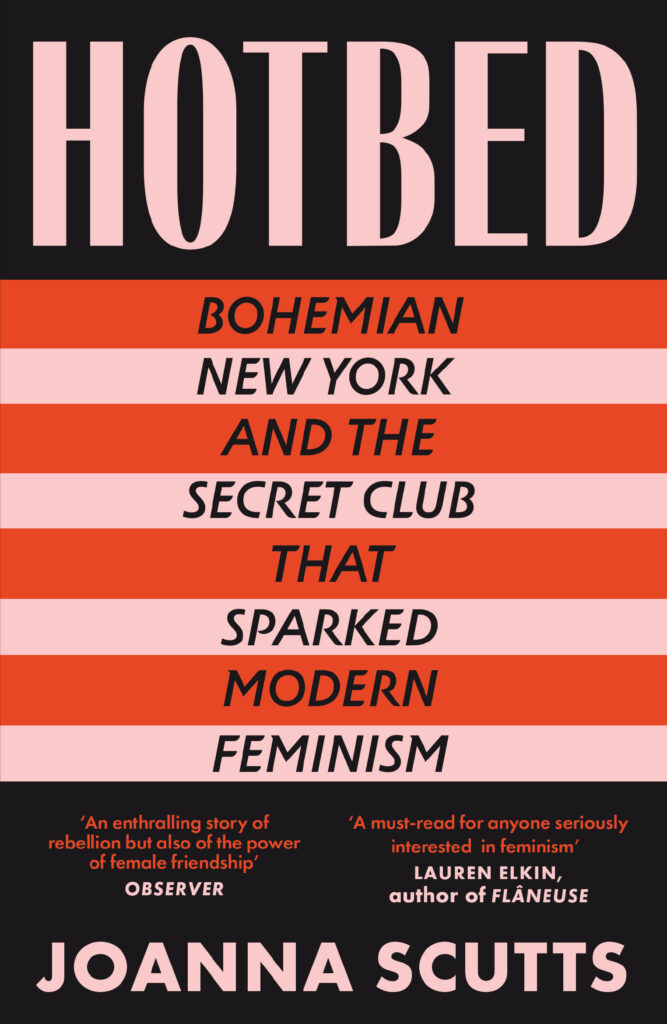

My book Hotbed took root in an exhibition of the same name, conceived to mark the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote in New York State in 1917, three years before it became law nationwide.

I was working with a small team to launch a new, dedicated center for women’s history inside the New-York Historical Society, the oldest museum in New York City, and we knew we had to mark the moment, but how?

The fight for suffrage was a long, complicated story, stretching back to the mid-19th century, but everyone knows the ending. Was there a way to tell it in a new, surprising way?

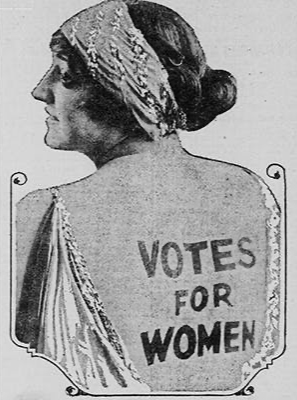

Dorothy Newell and 'Votes for Women'

We found the seed of our answer in a photograph dating from 1915, in which a young woman, an aspiring Broadway actress named Dorothy Newell, turned her naked back into a billboard blaring ‘VOTES FOR WOMEN’.

At once elegant and risqué, this piece of political performance art went viral, 1910s-style, landing Dorothy on the front pages of local newspapers across the country.

Her prescient blurring of politics and entertainment, the bold use of her body to titillate and persuade, struck us as startlingly modern.

She was a symbol of a new, modern suffrage movement that harnessed the power of celebrity and mass media to push its ambitious agenda: a constitutional amendment that would grant every woman in the country the vote, all at once.

A new kind of activist and a new kind of woman

Although Dorothy’s mark on history was as fleeting as the words on her back, she represented a new kind of activist and a new kind of woman, who was fighting for freedoms above and beyond her right to participate in vote, and who increasingly, embraced the new label feminist.

We took Dorothy’s photograph as inspiration for an exhibition that would celebrate those women and their involvement in a kaleidoscopic array of battles for social justice.

Women’s rights were inextricable from workers’ rights, which were entwined with the battle against racism and segregation, and the push for peace against an impending world war.

At a time of extreme social inequality, rampant racism, and the concentration of power in the hands of a tiny minority, the need for change felt urgent.

Greenwich Village – a radical hotbed of new ideas

In New York, the most daring and freethinking men and women were gathering in the shabby downtown neighborhood of Greenwich Village—a radical hotbed of new ideas.

The social calendar was crowded with social and political gatherings, experimental theater and wild fancy-dress balls. Men and women sat up late into the night plotting intersecting revolutions in art, society, literature, and life.

They spent their time writing and giving speeches, acting in plays, marching at rallies, publishing each other’s poetry, and hopping in and out of each others’ beds.

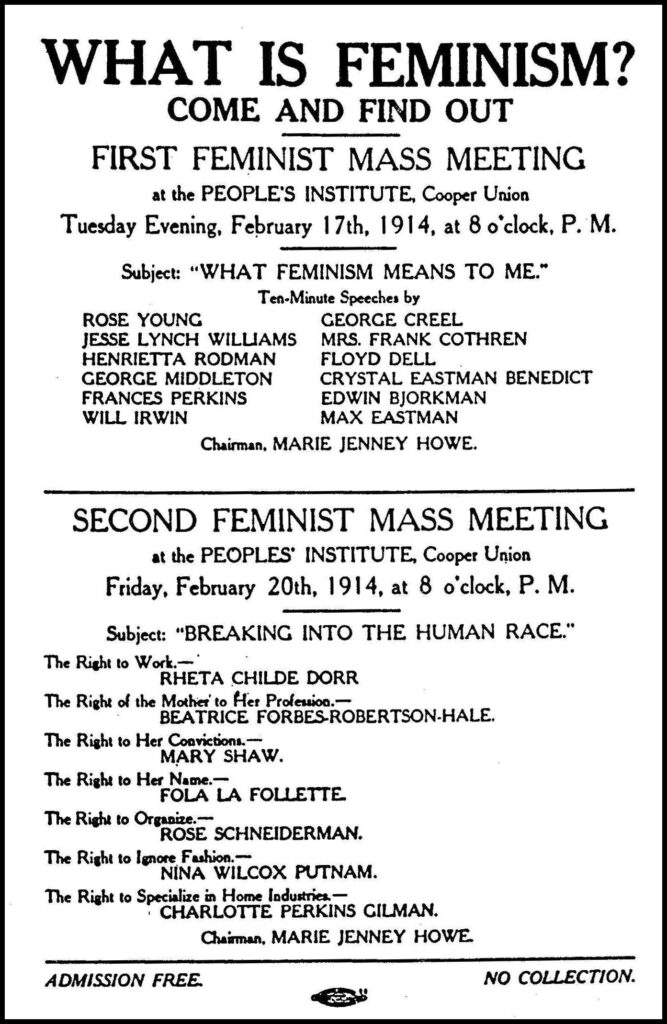

At the heart of it was a club called Heterodoxy

At the heart of it was a club called Heterodoxy, a gathering of feminist women who were famous or notorious in some way, whether for their writing, their activism, their professional accomplishments or simply the way they lived their lives.

Beginning in 1912, in the heart of Greenwich Village, the club met every other week, forging friendships that kept them entwined for more than 25 years.

Although it was official policy not to keep a record of their meetings—the better to allow for free discussion and debate—the club left a powerful mark on the lives of its members.

In 1915, they saw a fight they could win

For the women of Heterodoxy, suffrage was the beginning of the fight, not the end. Nevertheless, in 1915, they saw a fight they could win.

A statewide referendum was being held in New York, the first in a major East Coast state, and a bellwether for the national fight.

The campaign was a joyous, ubiquitous one: suffragists pasted up posters, made films, and took over Broadway theatres; they marched in the streets; scattered leaflets from biplanes and limousines; sold placards, pins, banners, badges, pencils, fans, jewelry—anything that could carry a Votes for Women logo.

They went to factories to persuade the men that women’s suffrage would increase workers’ political power, and they threw lavish fundraisers in ballrooms garlanded in sunshine yellow, the color the state organizers adopted for this push. It was three solid months of pageantry and optimism. And then, they lost.

Suffrage was the beginning of the fight, not the end

In late 2016, as our team of curators and designers mapped out the narrative and the look of our exhibition, we were cautiously optimistic that our opening would be buoyed by another historic victory: the election of the United States’ first woman president.

Hillary Clinton accepted her nomination in an all-white pantsuit, a nod to the visual style of the movement that had laid the groundwork for her nomination a century before.

Despite misgivings about the ability of one person to tackle the country’s innumerable challenges, we still felt, as those campaigners must have a century before, as though we were about to take a big step forward.

And then, of course, we lost too. That glass ceiling we’d cheered when it digitally shattered at the convention held firm, after all, and it hit us like concrete.

I remember sitting with my colleagues at lunch the next day, a grey November day when the whole city seemed to be walking around in shock, and asking ourselves whether there was any point in our work, in trying to tell true stories about American history when lies and myths held so much power.

History is a mass of untold stories

But the truth is, history is a mass of untold stories, especially if you are looking for the marginalized people, those elbowed off the simple, straight, masculine-heroic paths.

And there is hope in those stories. I found hope in the way the women of Heterodoxy weathered setbacks and disappointments, persecution and ridicule, and kept going, together.

And there is hope in those stories. I found hope in the way the women of Heterodoxy weathered setbacks and disappointments, persecution and ridicule, and kept going, together.

There wasn’t space in our exhibition to tell the individual stories of this remarkable group of women who came together to dream of what might come beyond the vote, beyond equality, beyond anything they could see around them.

I hope that in my book, Hotbed: Bohemian New York and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism, I’ve done justice to those dreams—and ours.

The dazzling story of the early feminists who blazed a trail for the movement’s most radical ideas

In downtown Manhattan in 1912, a group of women gathered, all fired by a desire to change the world.

This was the first meeting of ‘Heterodoxy’, a secret social club whose members were passionate advocates of women’s suffrage, labour rights, equal marriage and free love.

Hotbed is the never-before-told story of the club whose audacious ideas and unruly acts transformed an international feminist agenda into a modern way of life.